10 The Community Builds, 1900-1950

Preface: Class of 1902

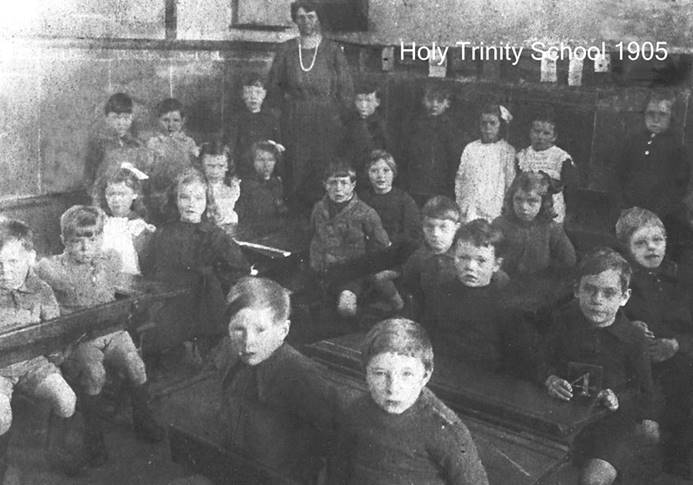

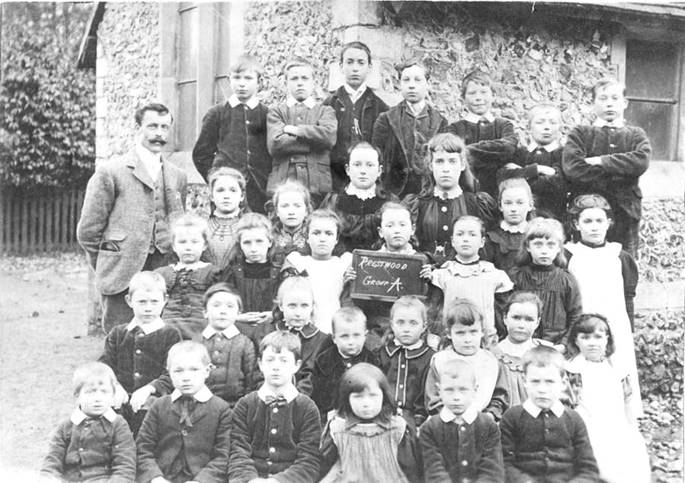

In the previous chapter was shown a picture of a Church School class of 1902. Later in this chapter is a photograph of another class in 1905. These were children born just before or around the turn of the century, their birthdates clustering around an average of 1895, their ages in 1902 ranging from 1 to 15. They represent the future of Prestwood at the very beginning of the twentieth century, a time of huge technological progress and massive social upheavals, none of which would have been foreseen by these children at the time, who must have accepted that things would be for them as they had been for their parents and grandparents, the people we have visited in detail in the last two chapters.

We are able to identify most of the children in these two class photos. They are mixed classes of 34 and 35 pupils respectively, with boys comprising about sixty percent. Each class had a mix of ages from the oldest to the youngest, but families were kept together, brothers and sisters in the same class. They do not represent a cross-section of the community at the time, as their fathers' occupations are better than average - a third were proprietors of local businesses and only a quarter were labourers or other unskilled workers. The children of farm labourers less often got the chance of being sent to school, partly because of the mobility of this section of the population and partly because they were needed from an age often as young as four to help contribute to meagre family incomes. (This would change within a few years with the coming of the first council school, as we shall see below, heralding universal education and, later in the century, a universal health service and welfare state, the two great reforms in the 1900s.)

But the biggest event that was about to unfold for these children was no respecter of social class. Most of these children were of the prime age for being called up when the first world war began in 1914. At least two-thirds of the boys saw active service. Sixteen percent would never return. One in six. Count them along the rows in the two photos and replace with gaps: the missing, "killed in action". This was what the whole community looked like by the end of war in 1918. Most families were of six or more children; most now had a gap where now there was only grief, and which would take time, much time, to heal.

Whatever was felt, however much time was taken to mourn and create memorials, the community nevertheless had to survive and economic activities and social life had to continue. The age of marriage in those days was densely clustered around twenty years old, especially for girls. The time of the first world war was therefore when most of the members of these two classes would normally have been expected to marry. Of the 37 children we can trace through later records, seven were married just before the war, only two during the war itself, and 28 afterwards. So for this generation, even for the survivors, marriage had to be postponed for up to four years. In time, over the decades, this would become no more than a blip in the statistics for the age structure of the population, but at the time it must have meant privation and anxiety, and sometimes physical loss. For the most part, despite the war, these people would lead the kinds of lives that might have been expected in the light of the technological changes then already moving forwards, although, especially for those boys who witnessed the horrors, the shadow would always remain. On average, the boys who returned lived to the age of 78, the last to die having done so in 1991, aged 91. The majority even spent all their lives, apart from the war, in their local community - only 41% of those that could be traced had left the immediate area of Prestwood, despite the fact that the C20th was a time of high geographical mobility.

The following are those in the two school classes that could be traced in the records, although, compared to the records for the earlier century that have been used in the last two chapters, they are only sparse, lacking the rich material of the available censuses 1841-1911, so that often we known only when they married and, for the men, when they died. (Women on marriage took the names of their husbands, not given in the freely available records, so that they cannot be traced further in most cases. This information could be obtained but only at inordinate cost from the point of view of this history.)

John Cummings. Born 1897. Brother to Ivy. Married 1921. Died locally in 1979.

Bertha Groom . Born 1897. Sister to Constance. Married at Holy Trinity Prestwood 1918.

Fred "Chum" Parsons. Born 1891. Brother of Dora. Could not be traced.

Fanny Parsons. Born 1894. Sister of Dora. Married at Holy Trinity Prestwood 1912.

Ernest Albert Redrup. Born 1893. Brother of George. Married at Holy Trinity Prestwood 1912. Died locally 1973.

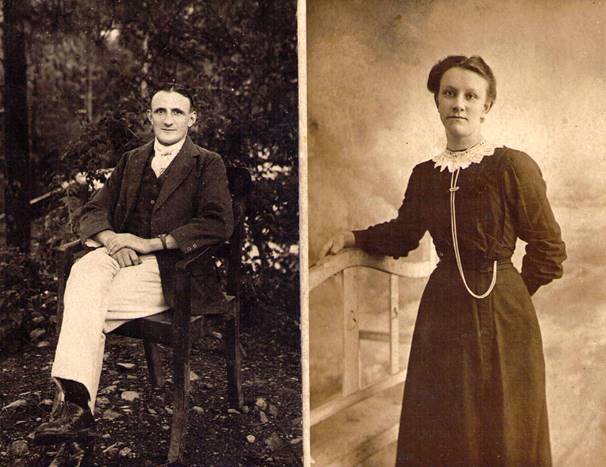

Eva Saunders (right). Born 1895. Sister of Winifred above. Married locally 1918.

(Winifred and Eva had two brothers, William (below) and Bertie (above), shown in the class photos, but they could not be uniquely traced.)

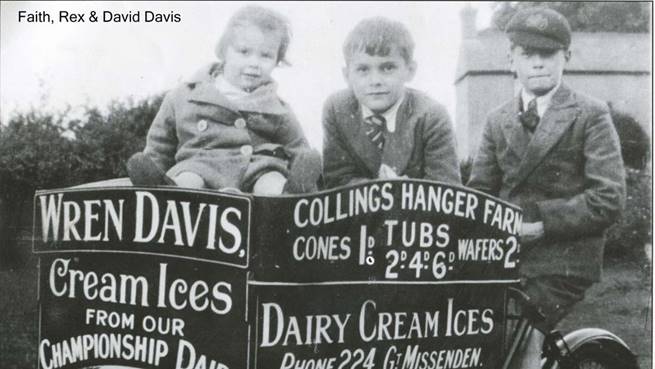

Emily Rose Stevens. Born 1899. Sister of Annie. At Holy Trinity Prestwood in 1923 she married the local farmer Wren Davis, whose farming company survives to this day. She died in 1987. The diary of her school years is extensively quoted below in this chapter. (A brother Rupert, who does not appear in the school photos, was involved in WWI and his account of this is also quoted later.)

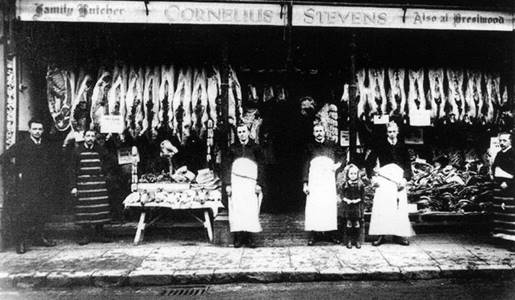

Sidney Stevens (left). Born 1898. Brother of Annie. Married locally 1925. In the 1930s he set up butcher's shops in Great Missenden, Denham and Aylesbury. He lived at The Limes in Prestwood in 1947 and died in 1970 at Aylesbury.

Isabel Elizabeth Timpson. Born 1899. Sister of Frank. Married, Holy Trinity Prestwood 1925.

Edwin Timpson (left). Born 1896. Brother of Frank. Killed in WWI.

Maud Wright (lower girl ). Born 1900. Sister to Sidney. Married at Holy Trinity Prestwood 1922.

In the 1905 photograph is also shown the headmaster of the school, William Henry Pitt. He had been born in Headington, Oxfordshire in 1865 and married Amy Charlotte Hannell of Great Missenden in 1900, who in the 1891 census is shown as a housemaid at Prestwood Lodge, where her father had been steward for twenty years. Pitt remained headmaster from 1900 through 1911 and was also organist at Holy Trinity Church during this time. Amy also taught at the school and is shown in the 1902 photograph. Both William and Amy died in 1942, having experienced two world wars.

Development in the Early Twentieth Century

In place of the vanishing horse came buses, lorries, vans, family cars, motor-cycles: nearly 1 million of them by 1922, more than 2¼ millions by 1930.

David Thomson “England in the Twentieth Century”

In 1900 Prestwood and the surrounding area was still in the horse and cart age.

"Water came from wells, it was without a sewage system and the village was lit with oil lamps. The roads were of flints or granite chippings. (Clarke, n.d.)

The Great Missenden Parish Council had been founded in 1895. Its early deliberations centred on allotments (particularly important during the First World War when food became scarce) and recreation grounds, the state of footpaths and roads (including obstruction by carts and herds of farm animals), wells, provision of a horse-drawn fire engine and a night soil cart (for collecting human excrement from privies and cesspits, often used as fertiliser - an early example of recycling). The first piped water came to Prestwood in 1902. By 1906, moreover, the motor car was having an impact and the Council decided to limit speeds to 10mph in the interests of safety. Driving was fraught for drivers as well as pedestrians, with narrow un-tarred roads, dusty or muddy according to the weather, and sharp bends. As early as 1915 the Council had to deal with complaints of vandalism to Prestwood Recreation Ground and Church Path, which were referred to the police. (Clarke, n.d.)

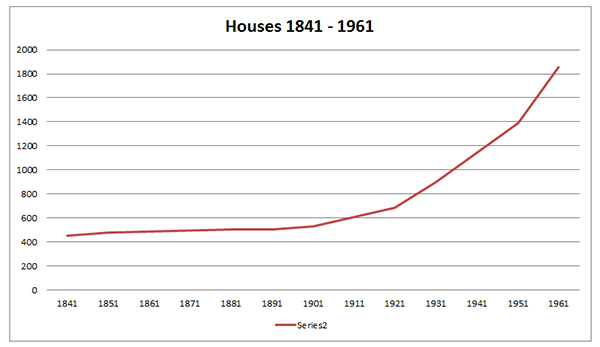

Even in 1900 one could still indicate individual houses and cottages of the parish on a small map without too much difficulty. By 1950, however, tracts of housing, whole estates, had come into being, making substantial areas of the map grey. The graph below, for Great Missenden parish, including Prestwood, shows the steep growth curve.

While Great Kingshill, Bryants Bottom, and the Perks Lane development were all part of this expansion, the greater part of the new housing in Prestwood Parish was in the village of Prestwood itself, especially close to or along the High Street (including several shops and a Post Office), on those fields that in the previous half-century had just been enclosed from Prestwood Common, and also along Wycombe Road and Nairdwood Lane leading south from the High Street. Initially these roads were little more than cart-tracks, sometimes with grass down the middle, although after the First World War and the growth of motor traffic they soon had to be upgraded to tarmac.

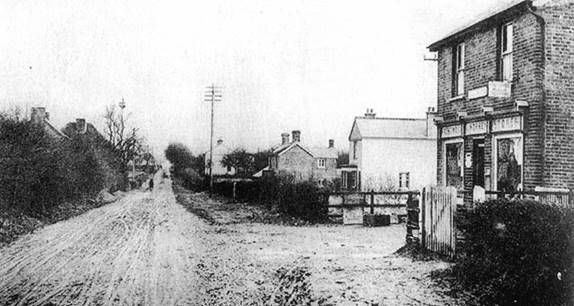

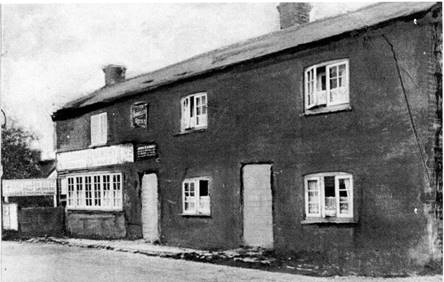

Picture taken early 1900s from the west end of the High Street, showing the Chequers Inn on the left and the first few buildings along the High Street (right). Wycombe Road begins on the right.

Picture taken c.1915 from just east of the Chequers, with Leslie Morren's "Prestwood Stores" and Post Office on the right, and showing the rutted condition of the muddy road. Morren's is now a private house, Maple Cottage, with Zoran's Bakery built in the gap between it and the next house, Excelsior Cottage, built in 1911 (see below). Leslie Morren had married Miriam Groom, a daughter of Solomon Groom, in 1906. After the Morrens the Post Office was run by Mr and Mrs Crook.

The Chequers 1911

Montrose (1910) and Belmont (1911) Cottages (110-116 High Street). The new brick-built tall houses had a distinct utilitarian "square" architecture, contrasting with the flint cottages of the previous century.

Arlington Cottages built 1911 (102-108 High Street).

Excelsior Cottage (1911) has a more decorative exterior. Zoran's Bakery next door is of much later date

Chestnut, Christmas and Drover's Cottages (133-143 High Street), part of post-WWI development

Maple Cottage (125 High Street), another post-WWI house

September & Ivy Cottages (77-79 High Street)

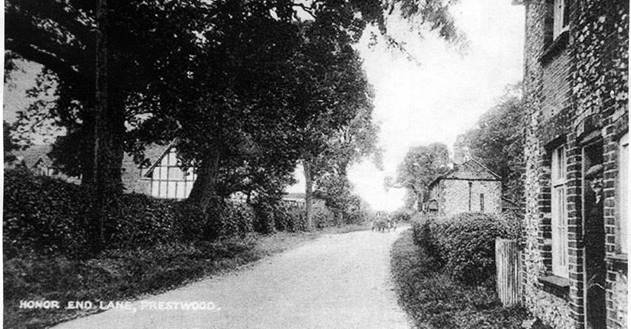

From 2,166 in 1901, the population of Great Missenden parish – which included the majority of Prestwood parish residents – more than doubled to 4,464 by 1951. Most of this development in Prestwood itself was smaller affordable housing in brick, a better quality building material than the traditional flint, although lacking the same visual character. (While one might bemoan the loss of an endemic building material like flint, one must remember that Prestwood was also a major brick-making centre, so that this also maintains historic associations and links with the native geology, even if many of the bricks used actually came from elsewhere.) Larger houses were built at Perks Lane (itself a new road) and the Grimms Hill estate just outside the boundary at Martins End – lining the road down to Missenden with well-spaced quasi-mansions with planted lawns and trees and sweeping driveways for their new cars. Nanfans was also enlarged as early as 1903, on the basis of plans by the young architect Giles Gilbert Scott, who was later knighted, like his father of the same name, designer of London’s Albert Memorial. North of Nanfans on Honor End Lane another large property, The Gables, was built shortly afterwards in mock-Tudor style.

Nanfans and its tennis court in the early C20th

The Gables

The Gables (left) was built in the early 1900s beside Honor End Lane, opposite the older cottages of Jasmine and Greenlands (in right foreground). The doorway in which the man is standing is now bricked up, but all these properties survive (see below).

Same view in 2018: many of the old oak trees to the left are gone, although one remains close to The Gables

The residences west of the former Prestwood Common became increasingly gentrified. Claremont House became Clarendon House Farm and was long the residence of the Beesleys. Henry Vicars Beesley (1879), a farmer, moved to Prestwood in 1905 when he married Hilda Groom (1886) of Prestwood in 1905, the daughter of the baker Alfred Groom. He ran a laundry business from the house, of which he was at that time a tenant of Arthur Bovill. He bought the house in 1919 after serving in the war. His father was manager of a furnishing business who lived variously in Berkshire, Kent, Bournemouth, Surrey, Barnstaple and Wycombe (Totteridge). The house remained in the family, being owned by his widow Hilda during the second world war after he died in 1940, and, after she died in 1965, by their children Miss Muriel Jessie Beesley (1905) and Gordon Wellesley (1914) into the C21 st . Part of the grounds was sold off for building more houses, such as "Berwyns" and "Silver Birches".

A new house "The Firs" (now Seymour Cottage) was built on Kiln Road somewhere between 1901 and 1911. It was occupied by a retired bank manager George Henry Quilter (1839) and his wife Mary Ann, née Bailey. The couple had no prior connection with the area, having lived previously in various parts of the country, and even for a time abroad, most recently in Brentford, Middlesex. Mary Ann had inherited income from property from her mother, so the couple were reasonably well-off. They were looked after by their unmarried daughter Gwendoline (1878). They also had an unmarried son Horace James (1870) who had qualified as an electrical engineer and in 1911 was living alone, employed as an engineering draughtsman, in Hampden House, Phoenix Street, St Pancras in London, a property belonging to the "Hampden House Residential Club". This was the meeting place of the Hampden Lodge of the Freemasons. One of the founders of this Lodge in 1892 was Lord Carrington, who lived at Missenden Abbey. (This building is no longer a masonic property - in the 1950s it was used as a British Railways hostel and it was redeveloped in the 1970s by Camden Council.) Horace moved to Prestwood to live with his parents in 1919, now aged 49, and the house was transferred into his name the following year. In 1921 he married Winifred Alice Clarke (1880), the daughter of a Yorkshire vicar. In 1911 she had been living as a governess for a family in Cambridge, but it was perhaps when she became a Red Cross volunteer in the First World War that she met Horace Quilter, although we have no concrete evidence that he was involved in the war. Horace's mother died in 1922 and his father moved out to live in Rochford, Essex, the county of his birth, where he died in 1926. Gwendoline remained with Horace and his wife at The Firs for the rest of her life and the couple had no children. Horace died on 20 October 1952, aged 82, and Gwen the following year. Winifred may have moved out of The Firs shortly after 1953, as she died at Harrow, Middlesex, in 1962.

At the end of 1952 Winifred had visited the County Museum in Aylesbury with a large collection of insects (mostly beetles) that had been put together by her late husband. This material, which is still housed at the museum, covered a long period of collecting from 1919 until just after the Second World War, almost all of it labelled as emanating from Prestwood. He had been a member of the Royal (now British) Entomological and Natural History Society from 1919 to 1933, and had some connection with other coleopterists, as some featherwing beetles he collected are found in the Sir Eric Ansorge collection at the museum, while some non-local material had the names of other collectors. One current resident of Prestwood who was a young milkman in the Kiln Road area in the late 1940s (Mr George Tyler) remembers Mr Quilter as a very private man, the family keeping very much to themselves, although he was seen around the village with a “butterfly-net” from time to time. Over half of the collection was made in his first five years in Prestwood, 1919-23, after which there were several years with no additions. Until 1934 most of the dates were at weekends, but after then weekdays were just as frequent and numbers of specimens increased markedly, perhaps indicating that he retired from work that year (when he would have been 64).

The most significant new building in Prestwood, however, was the imposing Denner Hill Studio and house built for himself by Robert Colton (1867-1921), an architect and sculptor, on the corner where the private road from Newhouse Farm enters Hampden Road. Erected about 1900 in the so-called “Arts and Crafts style”, it is now a listed building because of its architectural interest. Colton was President of the Royal Society of British Sculptors and Professor of Sculpture at the Royal Academy from1907 to 1912. The studio, which is very light and spacious, with a large “picture” window, has since been used by various artists.

A major expansion of housing also occurred at Bryant’s Bottom, where the former activity based on the working of the Denner Hill stone (still going strong with six stone-cutters in 1905) soon disappeared. Massingham, in 1940, decried this invasion in lyrical terms:

No sooner had this dingle fallen asleep at the foot of a curvilinear spur than the bungalows crept down upon it. They squatted just inside its portals as though afraid to commit themselves to the loneliness of its depths and with as much congruity to the scene as the sheep that still graze on the down above the wire-fenced enclosures would have if each were dressed in a bib, tucker and a pair of spectacles. They have taken the land, which is part arable, part sheepwalk, but never will they settle into it. At the other end of the Bottom gipsies were camping under the first trees of the wood that abuts on the fallows. Their painted caravan stood by and a brass-knobbed knife-grinder beside it as though the caravan had dropped its calf, while blue smoke from the camp-fire garlanded the glowing boughs of autumn. A more fantastic contrast between one end of Bryants Bottom and the other could hardly be conceived. The wanderers belonged, and for ever through the ages; the settlers would be foreigners until their gimcrackery fell to pieces.

Massingham was equally scathing about the development at Great Kingshill “ on its enormous green ”, about which he wrote

Sterile uniformity, sentimental stylelessness wipe out its identity, and this nondescript character makes the labyrinth of intercrossing roads through a country and a soil (clay-with-flints) dull at the best of times, a nightmare.

He saw the “ destruction of rural individuality ” as part of a general trend towards uniformity in the C20th century. What would he, one wonders, think today? Not everyone shared his jaundiced vision, however, and at least one minor celebrity chose to live at Lime Tree Cottage near Cockpit Hole and at The Laurels, Spurlands End Lane, in the 1930s and 40s. He was Laurence Walter Meynell (1899-1989), a very prolific professional writer of crime fiction, children's books and miscellaneous non-fiction (much of it under various pseudonyms). His wife Ruth was also a writer (née Shirley Ruth Darbyshire, under which name she wrote). She was originally Australian and also produced many works, mostly sentimental fiction and books for girls.

Further building expanded Prestwood on to the fields that had superseded the old common, now farmed by Jim Butler, who grew potatoes and swedes, kept chickens and heavy horses for carts and ploughing, the only buildings being wooden and corrugated-iron sheds ( information from Barbara Ridgley ). Ex-army huts from the First World War were put up along what became Sixty Acres Road (from the name of the large field it traversed, following the line of an old straight track across the common and down to Great Missenden via Angling Spring Wood). At this time the road was extremely rutted, full of pot-holes and with pits where Denner Hill stone had been dug. The track also ran past the Recreation Ground, which was still mainly heather and gorse scrub, the last remnant of the old common, part of it cleared by William Howard to serve as a playground. Where Blacksmith's Lane joined Sixty Acres Road from the High Street, Will Peedle, his son Ernest and his brother Ralph ran the coal and carrier business started by Simeon. A home for the district nurse Nurse Fincham, who acted as the local midwife, was built on the same road, on land gifted, according to the foundation stone, in commemoration of Allan Cameron Gardner (1869).

Foundation stone discovered when a house on Sixty Acres Road was demolished in 1995:

" This land was given for the nurse's home in memory of Allan Cameron Gardner The Chestnuts Prestwood "

Gardner lived at Chestnuts [formerly Prestwood Cottage] 1899-31.

Chestnuts c1910, when Allan Gardner lived there. Photograph by Mr JH Venn.

He had a private income and was born at Portsea Island, Hampshire. In 1881 he was a pupil in a small private school in Portsea. We know he had come to Prestwood by 1899, because in that year the banns for his impending wedding were read there, although the marriage, to Agnes Elise Drew, took place in Southwark, London. Agnes had been born in West Ham to Richard Drew, a "board correspondent" (an affiliate or honorary member of a board of directors who may communicate in writing rather than attend meetings), and Elise, a Frenchwoman. The newly-weds kept two servants in 1901. He appeared on the Electoral Register from 1899 to 1931, although in the 1911 census they were residing in Rochford, Essex. At that time they already had seven children - Harold Frederick (1900), Georgina Mary (1903), Florrie Edith (1903), Lily Jessie (1904), Nance Withers (1905), George (1907) and Patria Withers (1909). It seems that Allan Gardner was a naval officer, as the first two births were with British Armed Forces in Malta and Devonport respectively. The next three were in London. He appears to have won a medal in the First World War. They participated socially in Prestwood, because they contributed to the funeral of farmer Daniel Bedford in 1907. I have not been able to trace when or where either Allan or Agnes died, nor who provided the foundation stone (above). (The district nurse in the 1960s was Sister Coulson and the sheltered housing development Coulson Court, Nairdwood Lane, was named after her. Information from Lance Free.)

This expansion across the parish was fuelled by the railway to Great Missenden, plus road improvements and the motor-car, finally eliminating the labour from getting up the hill from Missenden or Wycombe. One can hardly imagine a greater change in aspect in just those 50 years than that from the pony and trap or occasional bicycle slowly ascending the gravelled tracks to the general stores on the nascent High Street, where houses and small terraces were scattered among fields and orchards, to the lines of smooth tarmacadam, along which streaked (relatively speaking!), between continuous houses and shops, box-shaped black Austin 7s refuelling at Crossroads Garage.

Shop of HJ Jordan (Crossroads Garage behind), High Street (corner of

Nairdwood Lane) c1916

Crossroads Garage in the 1950s

Crossroads Garage in 2006 (note that it had also taken over the former Jordan's shop to the right

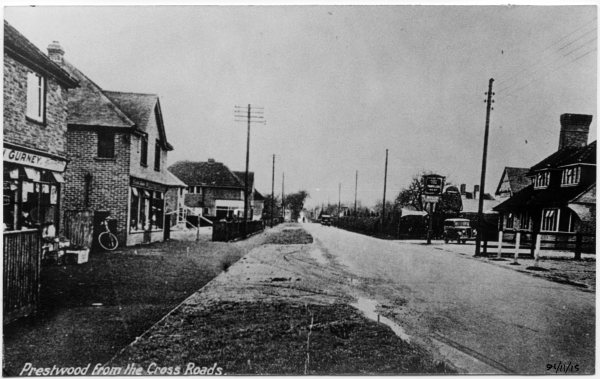

High Street, looking west from Nairdwood Lane corner, 1930s, Gurney's shop on left, Traveller's Rest (after being rebuilt in the 1920s) on right. The pub was demolished in 2014 and replaced by housing. Chiltern Garage Doors (no.37) now occupies Gurney's shop, while the shop beyond that (no.39) is now Scizzorz Handz (see below).

Same view in 2018.

Some things never change - the telegraph poles are still in the same positions!

As early as the 1920s the car was making its impact. The cycle repairers disappeared from Heath End and Sir Alfred Goodson at Peterley Manor was celebrated for his Rolls-Royce, when the first world war began, although motor traffic was still infrequent even in 1928, when one local resident remembers only about one car an hour bumping over the potholes of Wycombe Road (Holy Trinity Church, 1999, p17), while the bicycle, and indeed the horse and cart, continued as part of local traffic right up to, and through, the war.

Haven Stores (now

demolished, replaced by private house no.73 before 1955), Wycombe Road, with Austin

7, c1930

A film of a fancy dress carnival held on June 3rd 1922 reveals a strange mixture in the procession of pony and trap, horse and cart, bicycles, cars and even a motorcycle and sidecar. The procession went down Wycombe Road to Peterley, along there and back up Nairdwood Lane. The slow decline of horse-drawn traffic is illustrated by the fact that David Martin Nash worked as a wheelwright at Heath End up until the 1935, when he succeeded his father David as publican at the White Horse, and that William Peedle, succeeding his father Simeon, still worked as a carrier to Aylesbury until 1939.

Piped water had already been brought to Prestwood in 1902 (by the Rickmansworth Water Company), when the schoolhouse at the church was certainly equipped. Before then every cottage had access to a well or cistern, and water had to be carried by hand, sometimes in two buckets suspended on a yoke across the shoulders. Piped water, along with improvements to milk hygiene (see below) eventually reduced the incidence of disease and child deaths, but earlier in the century they were still an everyday tragedy. Emily Stevens, then aged 11, records in her diary that:

My little sister May was very ill during November 1910. …

April 8th 1911: Little May went to a nursing home at Amersham. …

May 19th: Little May died on a Friday at 10 minutes to 10 at night. Mother was there & [half a line scratched out]. She was buried at Prestwood Church on May 19th at 15 minutes to 4. We all went to the funeral. May was 2 years 19 days old.

(Over ten years later the Stevens family were still regularly visiting the grave of “little May”, as her niece Joyce Bennett (2004) recalls.

In March 1913 Emily also reports that school was closed for three weeks because of an outbreak of measles.) I am grateful to the late Rex Davis for showing me his mother’s diary, from which this extract and others below are taken.

World War I

The wider world had already intruded in an abrupt and particularly dramatic way during the first world war. Young Emily Stevens witnessed preparations in September 1913, when

The soldiers came to Great & Little Missenden … and some of us went to a service with thousands of soldiers. We saw an airship & an aeroplane while they were about here.

Unfortunately her diary ends abruptly with the outbreak of the war.

Another person recalled:

I can remember my father telling me about the First World War soldiers marching through Prestwood, and that they would come marching through in the morning and the columns of soldiers would continue into the evening. Soldiers were billeted in Prestwood and would spend their evenings in the Polecat, very often having one too many. Some of the soldiers were billeted with Granny Hildreth and, on their return from the Polecat one night, shot their rifles down the well which has remained cracked to this day. (Holy Trinity Church, 1999).

An aeroplane also crashed in the parish in 1916, which must have been a rare sight for parishioners when even the passage of a motor car was an event to be remembered.

Many families lost sons and husbands in the war. With the decline in woodland industries and loss of agricultural work at the beginning of the century, young men were often eager to enlist to escape unemployment. They did not know what they would face. The tragic losses in Prestwood are listed below.

R. Adams, sergeant in the Gloucestershire Regiment, died 1918; leaving a widow Dora Elizabeth at New Road, Great Kingshill.

Arthur Bob Bristow (1895), private in the Royal Fusiliers, died 1917. His mother Mrs J Bristow lived at Cross Roads, Prestwood.

William and Emma Chilton who lived in Bryants Bottom, lost two sons, Free (1884) in 1914 aboard HMS Aboukir in the navy, and Alfred John (1894) in 1917, a private in King's Own Yorkshire Light Infantry. Their father was a chair turner (see previous chapter).

Frederick Alfred Copeland (1891), private in the Royal Fusiliers, died 1917. His father Joseph, recently widowed, lived at Bordessa House, Great Kingshill.

Major HB Dresser, who had recently acquired Nanfans (and was to play a considerable part in the Prestwood community, see later in this chapter) lost his son Lieutenant Bruce William MC (1899) of the Royal Field Artillery in 1918.

Robert and Marion Gibbons of Prestwood (see previous chapter) lost two sons, Rupert (1882) and Frank (1892) on the same day, 21 October 1914, both privates in the Oxford and Bucks Light Infantry. Their father worked in the chair industry.

Stonecutter Harry Hailey, who lived in the row of cottages beside the Green Man, lost his son Ernest (1898) in 1917 at Ypres when he was a private in the Middlesex Regiment.

Arthur Janes, who had been a chair turner (see previous chapter), had become licensee at the Red Lion in Great Kingshill by 1916 when he learned of the death of his son Lance Corporal Albert Henry (1894) of the Oxford & Bucks Light Infantry, who had been active locally in cricket, football and rifle clubs. He also lost a brother Percy (1895) in the Machine Gun Corps in 1918, and two nephews George Albert (1893) and Frederick (1895) in 1916, the former a driver in the Royal Field Artillery. George's and Frederick's mother Bertha died, aged just 45, only a month after these two deaths, which must have overwhelmed her with grief, leaving her husband Albert, also a turner, without a wife as well as both sons.

The widow Elizabeth Langstone of Prestwood (see previous chapter) lost her married son Harry (1882), a driver in the Royal Engineers in 1917. A cousin of Harry's of the same age, son of the carter Thomas and his wife Ellen in Great Kingshill, private John Langston, also died in 1918 with the Manchester Regiment. He was married and living in Kent. Another cousin William (1891) who resided at Hazlemere died in 1917 as a Lance Corporal in the Canadian Infantry.

William Nash, farmer at Cockpit Hole (see previous chapter), lost his son Harry, a private in the Canadian Infantry, in 1916.

Simeon Peedle, the carrier and coal merchant (see previous chapter), lost his son Rupert (1893) at the age of 24 when he died at Passchendaele in 1917 as part of the Royal Berkshire Regiment. Rupert had married in 1915 and lived in Norman Cottages in Prestwood High Street. He left a widow Mabel and two daughters, Joan Mary born in 1915 and Margaret Elizabeth born in 1917. Joan, later Joan Axten, recalled how hard it was for single widows at that time, her mother having to supplement a small army allowance by taking in sewing.

Joan Axten, daughter of Rupert Peedle, in 2008 (from The Source HP16)

James and Elizabeth Phillips used to run the Royal Oak in Great Kingshill. Their son Albert G. (1883) was killed when a private in the Oxford & Bucks Light Infantry in 1917. He was married and lived in Great Kingshill, where he was a grocer in New Road. He was a bowler with the cricket club, a member of the football club, part of the Village Hall committee in charge of catering, and was an expert rose grower (Bucks Free Press, October 1917).

Private Albert G. Phillips died 17 July 1917

Edward and Minnie Redrup lived at 3, The Cottage, Prestwood. Edward worked as a hay binder (see previous chapter). They lost their son George Alfred (1899) in 1918, as a private in the Worcestershire Regiment.

Former stonecutter John Ridgley lived in Bryants Bottom (see previous chapter). He lost his son Charles Alfred (1883) in 1918, a gunner in the Royal Garrison Artillery. He was married and living in High Wycombe.

Former chair turner Thomas Saunders and his wife Lucy lived at Bryants Bottom and lost their son Ernest (1891) in 1917, a private in the Oxford & Bucks Light Infantry.

Free Smith, a stonecutter, had died young, leaving a widow Sarah who lived in Prestwood (see previous chapter). She lost her son Harold (1887) in 1917, when he was a private in the Grenadier Guards.

Gunner George Statham (1898) died in 1917 as a gunner in the Royal Field Artillery. He was the son of George Lilford and Charlotte Statham, who lived at Lilford Cottage, Prestwood.

Edward Timpson used to run The Polecat and later moved to Great Hampden and worked as a carpenter (see previous chapter). He and his wife Hester returned after 1900 to Great Kingshill. They were unfortunate enough to lose two sons when they were 21, William (1894) in 1915 at the battle of Loos (private in the Gloucestershire Regiment) and Edwin (1897) in 1918 (a corporal in the Canadian Infantry). At Loos the battalion was reduced from over a thousand to just 400 men, the rest gassed or shot.

In addition, the son of baker Herbert Groom of Ivycroft in Prestwood was seriously injured in France during the war. Lieutenant Hubert Stanley Groom (1890), who had been a schoolmaster, was with the Manchester Regiment. In a letter about the incident, it was written: Our men had advanced 400 yards beyond the front line and fell into a hotbed of Huns. They were charging with bayonets when Lieut Groom fell, shot by a machine gun through the right arm. On getting up and turning to leave the company, he got another shot [in the buttocks] ... Hubert Groom fortunately survived and lived until 1987.

A fascinating glimpse of life at the time of the war was given in a diary by Rupert Stevens (of the butcher family), quoted here with the permission of Mrs Faith Paul (née Davis).

" At the outbreak of the First World War, we had three shops in Wycombe. The White Hart Street shop, Desbro’ Road and corner of West End Street and Easton Street. ...

"All men of military age had to join the Home Guard and go to Priory Road Yard for Squad Drill. Sunday we had to take packed lunch and go to Didcot where we used to unload thousands of pick axes, shovels and wheelbarrows, or go on a route march round Penn or Tylers Green. Every three months we had to go before a Tribunal and my father would appeal and get Charlie and me off for another three months. The authorities checked up and found that Desbro’ Road was a small shop and not so much trade as White Hart Street. So Charlie was to be called up. I said that I was younger, fitter, and only had one child so I would go instead, while Charlie saw to the running of the shops. ...

"My father used to buy horses for the Army. They had to be about 16 hands, quiet, and about five years old. Once I went with him to Stokenchurch and saw a young horse. He asked the farmer if he could see his son ride it around the field, as he was afraid, so he got me to get up on it. The horse bucked and reared and ran out onto a stony road. I thought of Ethel at home and baby Doris, only a few days old. I was scared for my life and thought I should get my head split open.

"When I joined up I had to go to Cowley Barracks at Oxford. I was to go in the Infantry. I spoke up and said “Sir, I have two brothers with the Royal Field Artillery and I refer to the King’s Regulations which says brothers are to serve in the same part of the Services.” They had to put me in the Royal Field Artillery. On the Monday they gave me a railway ticket to Woolwich which is the HQ of the RFA. I thought I would like to spend the night at home so I went off next morning. Each day we had to march round and names and numbers were called out. My name was finally called out on Friday. Finally I was equipped with a uniform – which was just thrown at me. I couldn’t get my puttees right so I went and saw two High Wycombe men who were officers.

"While waiting to be called we had to dig a garden in Plumstead. Eventually I was sent to Abbey Park, High Wycombe, which was one of the HQs for The Royal Field Artillery. After two weeks it became an overseas camp and I was sent to Biscot Road, Luton for training. One day during a break I was with some other men and we were vaulting a horse when an officer came up to me and picked me for his team to go to India the next day. The next day an officer came out when we were on Parade and said I and five others were to report at once and go to Bath for a trade test as they were short of slaughtermen. One of our men had scabies so he was left behind.

"We were taken to an empty house where we slept on bare boards with our haversacks as pillows. While we were waiting we were marched up to the top of a hill where lots of the soldiers jumped over the wall of a gentleman’s garden. It was scandalous – they took tomatoes, strawberries and everything they could possibly eat! Finally we had our tests – a bullock each. We were watched by three men, one a civilian, one an Army officer and one a civilian expert slaughterman. When the Army Officer came up to me and tapped me on the shoulder he said “I can see you have done a lot of this.” ... I was sent straight off to South Shields where they did 100 bullocks a day to feed the troops in England. ... I managed to get a “Sleeping Out Pass” and I got Ethel and Doris to come and found three rooms. ...

Rupert Stevens (in white butcher outfit)

"Later, I was taken to what was thought to be a modern abattoir which was at the back of a butcher’s shop. They did not kill the cattle humanely with a pole axe, but bashed their brains in with a hammer. I took the hammer away and killed the cattle humanely. We had to take the hides to North Shields and put them straight in a freezer. I told the man they would rot and ferment but he took no notice. Six months later I had the ordeal of unloading the freezer. With the fermenting, rotten wasted hides, the stench was beyond description. This job lasted six months then I was returned to Luton and equipped for France. We set sail early one morning, it was snowing hard. Ethel came to see me off with a packet of nightlights. When we got to the station at Luton some of the men went berserk, starting snow-balling, smashing up the station, breaking windows etc.

"Before we went to France we were on parade one morning when an officer found that a Welshman had a spoon in his putty and he choked him off. The Welshman turned round, hit him under the jaw and knocked him out. There was another sergeant major, so strict and unbearable that some of the men decided to waylay him. They knocked him over and frogmarched him to the river and threw him in.

"When we were on the boat we were chased by submarines and we wore our lifebelts at all times and were a very long time getting to France, with all the zigzagging. When we arrived at base, we were met by another Wycombe man, Wally Baker, and some I did not know. I was put into an Ammunition column so I again pointed out that I had two brothers in the Artillery. I was thankfully sent to the Royal Field Artillery where I joined up with my two brothers, Bert and Sid. We were all posted together with the 33rdDivision Head Quarters Staff.

"I was posted behind Ypres as a mounted dispatch rider. The gun line was several kilometres in front of Ypres. Their headquarters was in a dug-out at Square Farm (same name as our place at Prestwood). I had to take messages at all hours of the day or night. I often met men from High Wycombe. I met the manager from the International and the Home & Colonial Stores. One day, on the way up the Ammunition Column, a man called out to me “Hullo Stevens”. He was Gilbert Mead of West Wycombe. We had a quick chat and on the way back I found he had been killed. When I was demobbed I went and told his parents that I was the last High Wycombe man to see him alive. He was killed in under half an hour from when I left him. I knew Hell Fire Corner and Dicky Bush inside out.

"Things were so bad as we pushed the Germans back that we were not getting our rations through. We picked up dirty food and biscuits out of the mud and scraped off the mud. They went down as good as rump steak – we were so ravenous. We had to take our water with us as the Germans had poisoned the water. We were not getting rum rations through and, as I had a terrible cold, I told the Quartermaster that I must have a good issue of rum that night. I was more nervous of my bad cold and sleeping out rough than of all the shells. The QM said “I dare not”. I said “If you can’t, I shall knock it off, but if you can get me some you shall have a Bradbury”. I had one pound note sewn in my bodybelt. He said “Where is your mug?” I took it off my bandalier and bought a pint of neat rum. I gave a small drop to brother Sid. I said ”As soon as I have drunk this, throw my horse blanket over me”. I went into a dead sleep. They had the horses off the line twice because of the shelling and I didn’t hear a thing. They had to shake me, even lift me up and jump on me, to wake me up in the morning. Strange thing, I never had a headache and my cold was much better!

"We drove the Germans back in one village. The French women ran out as we were riding along on our horses and gave us wine and tea, they were so delighted. I actually saw French people dig up money they had hidden from the Germans in their gardens and fields. As we advanced through Mormal Forest we rode over our own dead soldiers.

"One night another soldier and I had to drive a G.S. Wagon to take seven gunners up in exchange for seven gunners in the front line. While waiting for the exchange a Bomber came over an killed the seven men in front of our eyes. Instead of bringing back seven gunners we brought back their seven bodies. The next day we had the great ordeal of sewing them up in horse blankets and they were all buried in one trench with twelve others. I remember so well those nineteen men all buried in a trench.

"I happened to be on the sector when a delegate came across at Messens. Ceasefire on a twenty mile section and we couldn’t understand it. Later we heard that at 11 o’clock that morning an armistice had been signed on a train just near us. I remember the soldiers nearly went mad, jumping for joy and throwing their caps in the air.

"After the Armistice was signed I had an injury to my eye. We had a wonderful American doctor who said “I think you have done well to come through all this. Go to the Casualty Station and you should be in Blighty in a couple of days.” This was at the time of the great flu epidemic and I was detailed to take the temperatures. Of course I caught the flu which developed into pneumonia. During that time 40 were carried out dead with flu. I wondered if I would be the next. I lived on brandy and port and was unconscious part of the time. When I came round the Matron said that I must have been a steady sort or the brandy and port would not have had that effect. They sent Ethel a telegram as they thought I was dying. Then they sent another to say “Getting better, returning to England”. We were sent off to a French station on our stretchers and lay there waiting for the train. It was bitterly cold and a gale was blowing. I could not imagine how I would arrive home alive. How I prayed to be spared.

"Eventually we got on to the hospital ship. I shall never forget they asked each one of us where we would like to go. I said London. This really cheered me up as Ethel and Doris were there with Ethel’s father and brother and the Bennetts. When we arrived in England we were put on a hospital train in three tiers. I was in the middle bunk, the poor man at the top was so bad he kept being sick on top of me. In fact, they had to pull up at Chelmsford and send him to hospital there. I then realised we were not going to London and we went to Bradford. We arrived in Bradford at midnight. Crowds were waiting for us to welcome us home. They were shouting and singing “Welcome Home Tommy”. They put packets of cigarettes and shilling pieces on our stretchers. We were taken to an old workhouse, now an army hospital. When I was finally put to bed some man called out and told we newcomers that it was a “hell of a place”, but to us, from the trenches, the flu and the journey home, it was like paradise.

"The Orderly looked at my case card and found out that I came from High Wycombe and said “We have an optician called Dairy from High Wycombe here”. He fetched Mr Dairy who sent a telegram to Ethel and she and Doris came up the next day. Mr Dairy found them lodgings. I shall never forget my dear wife and child arriving. Doris pulling a little horse and cart. I felt overjoyed – I hadn’t seen them for well over a year. This hospital was a marvellous place. Ladies brought us jellies and played cards with us. I felt we were treated like Lords. Ethel’s brother, Frank had already been here with an ankle injury and his wife Edie, my sister, had worked here and helped to nurse him. Ethel and Doris used to visit me every day and Doris used to go round to the men in the ward with her horse and cart pretending to sell meat. One of them gave her a book. Almost all of these men in the ward died. I was allowed home for Christmas and released from the Army in January 1919 on account of having been in hospital for over a month. I went in to the Army A1 and came out C3. When asked if I wanted a pension I said “All I wanted was to get shot of all of them”.

Between the Wars

Until 1925, when the electric grid was first brought to Prestwood and paraffin lamps (and candles) began to be phased out (it would be another ten years before this happened in Great Kingshill), the only homes with electricity had been those who could afford their own generators, such as Peterley Manor:

The small building behind the gatehouse once housed a generator to provide electricity to the Manor House. Early, very thick glass accumulators, stored on shelves, were charged during the daytime and electricity passed to the house via a large overhead cable at night, so that the occupants remained undisturbed by the noise of the generator in the quiet hours. (Coulon, 2000)

HolyTrinity Church had electric lights fitted in 1930. Until then it had relied solely on candles and oil lamps, the smoke of which had so damaged the interior in fifty years that major renovation had been needed in the 1890s (Keen 1999a). Gas also became available in 1936, and the era of “domestic appliances” arrived to alleviate the time-consuming domestic chores that had been the reason until then for the large coteries of domestic servants employed by the wealthy families.

By 1939, then, Prestwood was a very different place in which to live (although it would be another ten years before the last of the main services - sewers - came to the village). It was also much more like other places in England than it had been in 1900. No longer was it the same rural backwater, but now it shared many of the facilities of the small town, and life’s horizons were beginning to expand.

Woodland industries

Despite all the changes, the greater part of the land in the parish was still agricultural or woodland. The demand for chair-legs from the beechwoods, however, was already in decline and rather than gradual continuous harvesting, woodland management was beginning to move into wholesale clearance of larger trees for other markets, often replaced by plantations of foreign evergreens, mostly larch. An example is provided by the sale of timber from Atkins Wood in 1905 by trustees of Miss Ann Daniels (who had purchased much land in this area around 1850 although not living locally, see Chapter 7). The sale of 100 loads of beech timber along with "lop and top" (the complete crop of this tree in the wood) fetched at auction £114-5s-4d, and the auctioneers Vernon & Son of High Wycombe wrote in their letter to the trustees (Messrs. Druces & Attlee) "Considering the somewhat depressed state of the chair trade we consider the prices obtained to be quite satisfactory". (It should be noted that in 1841, according to a bill of sale by William Grover to George Mason and James Gurney, the beech timber in the wood was valued at £456-15s-5d, so that the drop in value is very evident.) The wood was replanted to a mix of beech, larch and Sitka spruce, much of which was again harvested a hundred years later in 2013.

Atkins Wood in 2007 before the second clearance

There was still a timber yard in 1950 (Jennings on the High Street) and a wood-turner’s at Peter’s Close. Bodgers worked in Prestwood through the 1930s (such as Tom Gomme, Owen Smith), but the trade survived after the war only in even more rural areas such as Hampden and Speen.

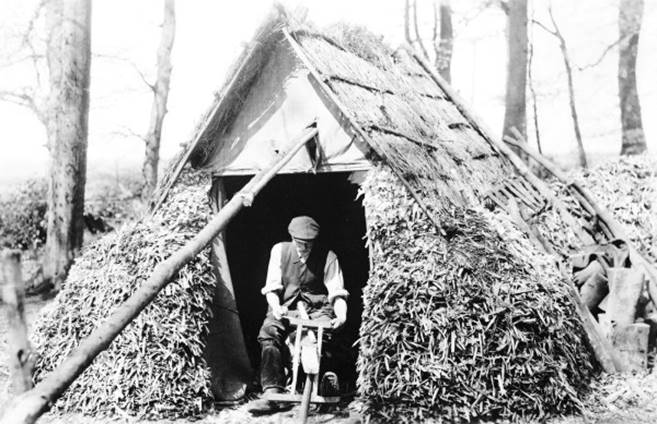

(Above and below) Bodger TH Gomme working at his hut in Lodge Wood 1929; above with a shave-horse, below roughly shaping a chair-leg with a hand-axe

One of the last bodgers, Owen Smith, son of a Denner Hill stonecutter (see last chapter) and his wife on their wedding day 1920. He looked after his widowed mother Emma until she died in 1914 at the age of 75.

Many of the beechwoods planted in early Victorian times nevertheless did survive and were now maturing to provide the scenery for which the Chilterns has become particularly renowned – although these swathes of fresh green in spring, cool shade in summer and deep gold in autumn that attracted the tourist were no more indigenous than the visitors themselves! In 1938 The Times was featuring the Chilterns as a site for a motor tour (itself a sign of the changed times), enthusing over “those matchless woods in such beauty in spring” and “the hundred hued veil they spread over the shoulders of the hills in the distance” (Prioleau 1938):

We went to Hampden Row and Hampden itself and Prestwood, all among the waiting beeches (they are finer just here than anywhere else), and all of it was worth while. This is a very pleasant part of the world at all times of the year: it should be at its best when a week’s rain has restored their natural light and colour to the tall trees.

Orchards

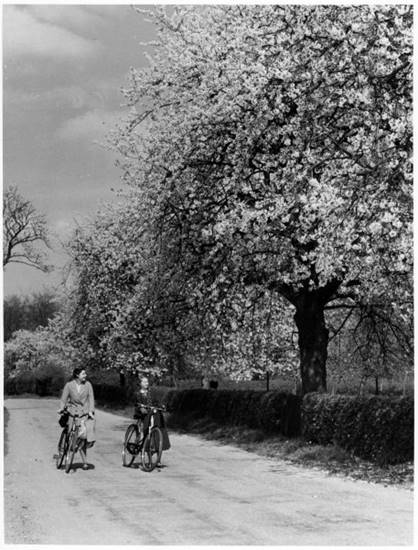

The last writer would appear to have come just too soon to see the flowering of the cherry orchards (“ from a distance they appeared like hills of snow; the twigs and blossom from one tree touched that of the next ” remembers a local resident quoted in Holy Trinity Church, 1999), or no doubt he would have enthused over these as well. Certainly tours were organised in charabancs from as far away as London to see the cherries flowering. Prestwood cherries were sufficiently well-known for Alfred Rothschild to nominate them as his choice for making cherry brandy, and there was a specific local variety known as the Prestwood (or Little) Black.

The orchards ... supplied the Leicester and London markets, when it was still possible to send fresh freight from Great Missenden station. Cherries in wooden crates sealed with cardboard lids were delivered to the station by horse and cart. … cherry picking coincided with the annual two week shut down of the Wycombe furniture factories, and many townspeople spent their ‘summer holiday’ working in the orchards . (Davis 2004)

Factory workers came at this time from further afield, too, the Midlands and London. The Prestwood Black was a "maz(z)ard" (apparently derived from the Old French word masere, although this referred to maple), a descendant of the ordinary wild cherry. On its own it produced small dark fruit that no longer suit the demands of modern supermarket. Mazzards were also used, however, as a vigorous stock on which to graft cultivated varieties. As well as Prestwood Blacks, orchards at Hampden Farm and near Prestwood Lodge also stocked another local variety “Nimble Tailor” or "Nimble Dick". The latest to fruit were the Merries (virtually the same as the wild cherry, from the French word merise), which included Prestwood Black above (also known as "Caroon"), saved for making local specialities like cherry pie (see Holy Trinity Church, 1999, p.23 for a local recipe for Bucks Cherry Turnover). A range of varieties were grown, each with different characters for different purposes, and many of these are endangered today in the age of mass production for the supermarkets. Those with particularly local associations included:

Alba Heart: black-skinned with dark flesh.

August Heart: large black juicy fruit with deep red flesh.

Bedford Prolific: another with shiny dark fruit.

Bigarreau.

Black Eagle: the only known specimen of this tree was discovered by George Lewis, surviving from a former orchard in the garden of Morris Randall in Prestwood. Cuttings were taken and propagated by Bernwode Plants. It has large sweet black fruit.

Black Heart.

Early Rivers: a particularly juicy variety.

Frogmore.

Goblin.

Lester: almost black with dark red flesh.

Napoleon.

Nimble Dick.

Prestwood Black: like the Black Eagle, this was discovered by George Lewis growing in a number of Prestwood gardens created on the site of former orchards, including that of Morris Randall. One surviving tree can still be seen on top of Denner Hill at Rickyard Cottage. This was probably the commonest variety grown locally, although not well-known more generally. It is a black dessert cherry.

Red Heart or Ronald’s Heart: large and heart-shaped, blackish with pale stripes and dark red flesh.

Strang Loggie: originally from the Channel Isles, very large with dark red skin and flesh.

White Heart: a large heart-shaped cherry with creamy-white skin turning mottled red on the sunny side and pale yellow flesh.

Nimble Dick cherries

As the fruit formed it was necessary to keep birds off, so that boys were employed for a few pence from dawn to dusk to bang corrugated iron sheets with large sticks, which must rather have spoiled the peacefulness of Prestwood at that time. There were not many wood pigeons around in the early C20th, as they were regularly shot, both as a source of food and to prevent them becoming a nuisance. Picking cherries involved special ladders (see Chapter 9). The fruit was collected in round wicker baskets with a concave base for stacking known as "sieves", capable of holding 24lbs of cherries. They were covered with paper and hazel sticks to prevent damage to the fruit. The end of picking was celebrated in local pubs with cherry pie suppers and pie eating contests.

Cherry orchards in flower alongside Heath End Road, Great Kingshill 1935. [Photo Ronald Goodearl.]

In the early C20th orchards existed both sides of Prestwood High Street, stretching north as far as the Kiln Common cottages and south along the Wycombe Road, most of this area now entirely covered with housing. A large orchard was planted to the north of Dennerhill Farm and lasted until about the 1960s. Although cherries, peculiarly suited to the soil here, were the mainstay, apples, pears, plums, damsons and cob-nuts were also cultivated, the latter often planted in the border hedgerows because they were not suitable as standard trees. Particular local varieties included:

Apples

Bazeley (“Best of The Lee”): which originated at The Lee, a small village on the hills across the Misbourne valley, and grown by most farms and cottages in this area in the C19th for making mincemeat, keeping its texture when cooked. It is a green cooker, turning yellow, that can also be used as an eater after storing.

Long Reinette (or Long Runnit): another variety associated with The Lee and local farms. It was a dessert apple stored in straw in barns to bring out at Christmas. The green skin is more or less streaked red and the shape is somewhat elongated, hence the name. When a new house was built on Pipers Lane where a remnant orchard apple tree stood it was called Long Runnets, a local version of the name of this variety.

Plums

Aylesbury Prune: a smallish blue-black dessert plum which grows on trees with rough twisted bark.

Cherry Plum: whose small round fruits are variously red, purple or golden-yellow, and whose flowers appear before any of the other fruit trees;

(Information on varieties of orchard fruit was derived from local informants and the catalogue of Bernwode Plants nursery.)

Cattle or sheep were routinely grazed in these orchards, helping to control the grass around the trees and making double use of the land. This practice is continued today in the orchard at Collings Hanger Farm.

Farming

The prosperity of farming reached a peak around 1900, when there was still a good mix of pasture and arable in Prestwood. Land under crops, however, steadily declined in extent until the second world war. Cheap wheat was coming in from America and the rise of motorised transport reduced the demand for oats and roots to feed farm horses. At the same time better-paid industrial jobs in the towns were becoming accessible to farm labourers and the cost of keeping them on the farms was increasing, again hitting most the labour-intensive arable farms. The hilly terrain and relatively infertile soil also prevented recourse to the huge fields of potatoes and sugar beet that at this time came to dominate East Anglia and the Midlands. Cropland was therefore turned to other uses, as pastureland, hayfields (especially Collings Hanger and Nanfan Farms) or to raise pigs, chickens, turkeys and game-birds.

Meanwhile New Zealand wool and lamb imports began to knock the bottom out of sheep-rearing, and most grassland was now used to raise dairy or beef cattle. The completion of the railway network, enabling the speedy transportation of fresh milk, had turned dairying into a much larger-scale activity than it was in the C19th, when herds were no larger than needed for purely local consumption of milk, butter and cheese. New legislation on hygiene also enabled better quality, safer milk to be produced, itself enlarging its potential market. TB was eventually eradicated by pasteurisation.

Although the Chilterns were not necessarily the same as other parts of Buckinghamshire, the figures for the area under different kinds of agriculture in the county in 1913 are still instructive. At that time, 61% of land was permanent grassland, 30% arable, 8% woodland, and less than 1% heathland. The clearance of heathland and the decline in arable are clear. The main crop at this time was wheat, closely followed by oats, with barley some way behind, and smaller amounts of beans, peas, potatoes, turnips, mangolds, and fruit. Druce (1926) was scathing about the large bare chalk fields with "scanty corn" or "flinty turnip fields"!

Wren Davis (1900) took over the farm at Collings Hanger on 25 October 1923. He was the son of Arthur Davis on Denner Hill. Wren took his distinctive name from the maiden name of his great grandmother and this was the name everyone used, although he had been christened Arthur Wren). By this time his father was a prominent local figure as a county alderman and magistrate, as he was to remain for the whole period between the two world wars, owning not only this land, but also Stonygreen Farm which had been sold by Mr E Stanford in 1910. The catalogue of the stock sale on this occasion (my thanks to Virginia Deradour for showing me this) gives an insight into the nature of a typical small mixed farm at the time. Animals comprised 13 cows, 34 lambs, an 18-month sow with 6 pigs, a horse and pony (in foal), 100 fowls, 6 turkeys, and 3 guinea fowls. The cows were of a variety of breeds – a shorthorn, a red cow, two cross-bred cows, and a brindle heifer all with calf, plus a pure-bred Jersey heifer, two shorthorn heifers, and four red steers. The main crop was hay, of which there were three 10-ton ricks for sale at £6 each. There were also two ricks of “White Tartar” oats (£7 together), and one of wheat and straw (30 shillings). Among sundry equipment to be disposed of, there was a brooder for chickens, a portable hen house, rick poles and pulleys, water barrel on iron wheels, a Ransome iron plough (28 shillings), a Howard iron plough, a Ransome ridge plough, a mangel drill (for planting mangel-wurzles as cattle feed), a Woods iron horse rake (30 shillings), a McCormick mowing-machine (16 shillings), a McCormick binder, a Bentall two-knife chaff-cutter (£1), a cake crusher and a winnowing machine (29 shillings and sixpence). Dairy utensils and a churn indicate that a small amount of milk was also produced. Arthur Davis himself was now raising wheat, fruit, game-birds, cattle and pigs on Denner Hill, assisted by his son Dudley. His son Richard still lives there today. The slopes are so steep that

before tractor power, only one man on the farm had the skills to turn a team of horses on the banks. Even now, tractors must be driven down the steepest slopes and not across to avoid tipping over (Davis 2004).

By the 1930s, however, Dudley Davis was using steam traction engines and threshing machines, contracting these out for extra income to other local farms.

Old Howard Bedford iron plough (on display at Peterley Manor Farm)

Wren meanwhile had to wait for the previous tenants, Arthur Grover and his wife, to build themselves a new house just to the north of Collings Hanger Farm, before he was able to marry and move into the farmhouse in 1925. The farm stock had been auctioned off in 1920 and reflected a very different business from Stony Green, with a focus on pigs and poultry. The pigs comprised 8 black and 7 white “porkets” (young pigs fed for pork production, now usually called porkers). There were 65 hens, a black Minorca cock and a pullet, 14 white Wyandotte hens, and 35 Wyandotte chickens. Finally there were three horses and a rabbit hutch (but no rabbit!). There had been cows, which must have been disposed of earlier, for the equipment for sale included milking equipment, a calf manger, rock salt and a cattle sling and pulley. There was also charlock seed, presumably sown as cattle feed. The main crops were, like Stony Green, hay and corn. These were cultivated with the help of a Ransome iron plough, a Pratt iron plough, a Ransome one-way plough, horse rake, winnowing machine, a Hornsby self-binder, a McCormick mowing machine, and a Knapp corn drill. Horses were used to draw the ploughs etc, and also for transport, with 3 farm carts, a spring market cart (with ladder, double seats and lamps), and a governess car (a light 2-wheeled chaise with side-seats).

Wren’s bride, Emily Rose (1900), was a daughter of Cornelius and Mary Ellen Stevens (see previous chapter and below), so uniting the two main farming dynasties in Prestwood. Wren and his new wife had taken over a mixed farm and continued to rear pigs and produce crops. Arable production was based on a five-year rotation: wheat one year, oats the next, roots (mangolds and swedes) and kale in the third year, barley in the fourth year, the barley being undersown with grass as a basis for the final fallow year of clover. The resting year helped regenerate the soil and the clover fixed nitrogen to provide a nutritious soil for the next wheat crop, which began the cycle over again. Hay was produced as winter feed, the ricks being thatched in the traditional way (see below on Lisley’s Farm). There was a cherry orchard beside the farm and another across the road behind the since-demolished Collings Hanger Cottage.

Within a couple of years, however, Wren purchased two cows to begin what was to become a successful high-quality dairy business. Milking was carried out by hand until 1944. Traditionally local milk was carried around in large cans, customers collecting it in their own jugs. Wren Davis was the first in the area to introduce milk bottles, washed at this time in the kitchen sink. He was also one of the first five dairy farmers in the country to be licensed to produce Grade A milk. His first delivery in September was to two customers, charging 3d a pint (approximately 1p in current coinage), but, with an emphasis on modern hygiene, the business soon snowballed from there. His son Rex remembers making deliveries of milk and ice-cream on a solid-tyred bicycle, carriers back and front, in the thirties. In 1930 Wren Davis won third prize in the All England Inter-County Competition for clean milk, already had a sizable herd, and employed a good number of dairymen.

Milkman for Wren Davis, late 1930s

Jersey cows in Clay Markings field belonging to Wren Davis farm 2001

Wren and Emily had two daughters, Faith and June, and two sons, David and Rex. When he died at the age of 67, the church at Great Hampden was decorated for the funeral with wild flowers. The farm was left to his sons Rex and David and it is David's daughter Virginia who runs the farm to this day.

Rex Davis died in 2009 at the age of 80. In her funeral address Virginia Deradour remembered that he was seriously ill at the age of 9 with meningitis, missing a year's schooling, although he still managed to pass for the Royal Grammar School in High Wycombe and became head boy. He never married but engaged in community affairs, supporting several charities and purchasing an organ for Great Hampden Church (where he was a bell-ringer). 300 people attended the funeral and the coffin was pulled by his pet donkey Neddy.

David Wren Davis (1926) very early became an advocate for steam traction engines, as used on Denner Hill, even riding back from his wedding reception with his wife Jean on one in 1957. The engines were used for ploughing (one at each side of a field would draw a plough across between them), and many other jobs such as clearing trees. They were often hired out to other farmers. and his enthusiasm lasted to the present day, long past the machines' practical usefulness, superseded by the petrol-driven tractor. His son drives steam engines as a hobby to this day and the farm every year hosts a nationally-known Steam Fair, attracting machines driven from fellow-enthusiasts from far afield.

Steam traction engine leaving Collings Hanger Farm 1999 (photo by Rex Davis)

The Stevens family had started a new farm, Square Farm, a former cottage at the north-west corner of Prestwood Common, around 1880. Cornelius Stevens had taken this over in 1895, breeding pigs, beef cattle and shire horses, and maintaining an orchard. Cornelius Stevens' daughter Emily described in her diary in 1910 how

At the flower show at Prestwood, Father had three prizes for his horses, a first for Prince Edward and another first for Peggy; also a second prize for Albert’s horse; Sidney [one of her brothers] had the second prize for his wood-work which he did at school. I put a pinafore and wild-flowers in, but did not get a prize. ( She subsequently describes further prizes for Prince Edward and Peggy at Tring, Halton and Aylesbury shows.)

Cornelius later built a bacon-curing factory and opened a butcher’s shop. His wife Mary was a local girl. From 1910 onwards he lived at a large house, The Limes (since demolished) in Wycombe Road, on the site where Hildreths Garden Centre now stands. (The large oak tree that stood at the front of the house survives to this day as one of the largest and oldest trees in the parish.)

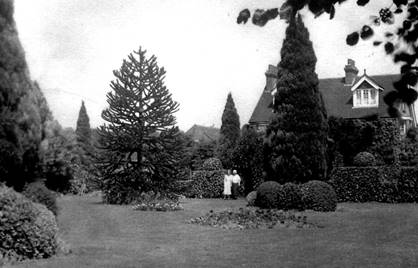

The Limes from the garden

His mother had died in 1903 and his father got remarried in 1905 to the widow Ellen Ives, but he died ten years later on 30 March 1915, his executors being Ellen and Cornelius. Cornelius's family of 12 children were then all grown up and dispersed, but family solidarity was still strong, and most of them would still attend Holy Trinity church regularly, where they would all sit together and Cornelius would hand round sweets to the grandchildren (Bennett, 2004). The meat business was highly successful. All seven of his sons became butchers, with shops in towns over a wide region of the Thames Valley area. After Cornelius died in 1932, his four sons Arthur, Alfred (living at Springfield just outside the southern tip of the parish, and who had married Alice Clarke of the Moat Farm family), Charlie, and Rupert took over the factory as C. Stevens & Sons, enlarging its scope to manufacture pork pies, this venture becoming a major employer in Prestwood for thirty years. They also set up a branch in High Wycombe (White Hart Street).

High Wycombe branch of Stevens butchers. Rupert Stevens is second from right.

When the Stevens factory was closed in the 1960s, a field to the east of the factory was used for ‘blood pits’ – deep well-like shafts, 30 or 40 feet down, for disposal of offal. The field was later used as the playing-fields for Clare Road school (built 1966) and the pits had to be capped with concrete because the ground above kept subsiding into them. A grassy dell between Collings Hanger Farm and Prestwood Lodge was similarly used. When the Lovells estate was built across the land this area had to be left as open grass because it was unsafe to erect houses on it. It is now known as Greenside (Doel 2000).

Greenside 2014

Pheasant-rearing had started in Prestwood towards the end of the C19th and became particularly prominent through the first half of the C20th. The Davis family on Denner Hill raised both pheasants and ducks. Apart from them, the Eltringham brothers (of whom Hugh Cyril lived in Prestwood, the other in Great Missenden) started up a major business Gaybirds Pheasant Farm on Moat Lane before the First World War, employing over a dozen men. They produced eggs and chicks for shoots all over the country. It was still operating in 1955 but seems to have ceased somewhere around the 1960s. H. Cyril Eltringham published a book " Pheasant Rearing: practical management and modern methods of rearing as practised on the Gaybird pheasant farm " in 1955. He also played tennis at Wimbledon between 1913 and 1922 and was a member of the Royal Flying Corps in the Second World War. He was on the Shooting Advisory Committee of the British Field Sports Society 1960-61.

Gaybirds Pheasant Farm c1912.

Back row: Ernest Tilbury, Bert Beeson, John Wixon, ?, Cyril Groom, Tom Wixon, John Ward, Clem Groom, ?, Alf Field, Dick Wells, George Clarke, ?.

Front: ?, Cyril Eltringham, Mr Hunting, Mr Driscol

Herbert Groom , eldest son of Solomon Groom who had started the brickyard along Honor End Lane, had been a baker, but in 1915 he took up horticulture and breeding poultry. He exhibited his own variety of Wyandotte fowls ("Groom's strain") and won many prizes. He set up the Prestwood Horticultural Society and took an active role in village affairs, being a manager of the Moat Lane school, a trustee of Prestwood Village Hall, a parish councillor and a special constable. Central to his life, however, was his church, the Baptist Chapel, where he played a central role like members of his family before him. He died in 1936, aged 76.

Herbert Groom

Pedigree pigs were being bred at Cherry Tree Farm by Ian Purdie from 1924 until the war. He died in 1943 when a lieutenant in the RAF (from natural causes). He had been a judge of pig breeds at Smithfields and secretary of the Princes Risborough Farmer's Hunt Ball.

The small Hampden Farm on Greenlands Lane was bought in 1919 by the builder Mr Parker. It produced and delivered milk, and fattened pigs for the Stevens factory.

The Priests took over Ninneywood Farm about 1935 to produce beef cattle. Their son John owns the farm to this day. His mother was another daughter of the Stevens family. The Priests had farmed to the south of Prestwood for generations. In 1851, for instance, a John Priest, then aged 31, occupied a 32-acre farm at Little Kingshill, very close to Prestwood. John Priest's father was a tenant at Ninneywood at first, but was able to buy it in the 1950s. John Priest relates their history:

" They built up a small herd of Guernsey cows and sold the milk to Wren Davis. In the 1960’s I started keeping pigs. I kept Wessex Saddlebacks and crossed them with Landrace and Large White. I used to keep them outdoors where they farrowed in huts and to start with I sold them as weaners at eight weeks old. In later years I had a farrowing house built and fattened them up to pork weight.

In the mid 1970’s my father gave up the milking herd, and by the 1980’s as the profit went out of pigs I decided to give them up and start a single suckled beef herd. We still have the beef herd, Charolais and Limousin crosses. The calves remain with their mothers until they are weaned at nine months old. When they reach 18 months we sell them to another farmer to fatten. We hire a Limousin bull from June to September and our calvings start in the following spring. All the food for the cattle is home grown , approximately 1000 small bales of hay and 200 large round bales of silage for the winter. The cattle remain outside all the year round but have a large barn to go under in the bad weather.

The farm is about 50 acres, including a small section of woodland. We don’t use any sprays and very little fertiliser. The fields are divided by thick hedges and provide cover for the diverse wildlife including badgers, foxes and deer. We have two ponds on the farm attracting moorhens, dragonflies and grass snakes. Ann keeps chickens, as free range as the fox will allow, enough to provide us and our friends with eggs.

It has always been a job to make much money on a small farm and even at the present time the government is encouraging farmers to diversify, so back in the early 1970’s we started a photographic business. We are still running this business and trade under the name of J. P. Photography. Nowadays my wife Ann does most of the photographic work, which consists mainly of press, public relations and portraits. You can see examples of our photographs on our web site – www.jpphotography.co.uk.

The large farm at Andlows, originally owned by the Honnor family of Great Missenden (Missenden Abbey Estate), was worked by the bailiff Theophilus Beeson on behalf of Major Samuel Day after the first world war, and by Mr Beeson later in the twenties and thirties.

This appears to be Little Salmons, the field behind Andlows Farm. Taken in 1921 this photograph shows the hay-stooks but begs many questions, such as who were the couple and the purpose of collecting the leafy twigs the woman has in her basket?

The farm originally extended to the other side of Angling Spring Wood (another part of the Honnor domain), but the two fields there were sold off to the Readings of Town End Farm in Great Missenden in 1938. The main ride through the wood had been a route for farm carts between the two parts of the farm. The main farm was rented from 1939 by Joseph Edward Garner, who had been born in 1901 in Aylesbury.

Farm labour was eased in the 1930s by further mechanisation. As well as on Denner Hill and at Collings Hanger Farm, steam engines were in use at Hotley Bottom Farm by Rupert Taylor, who also hired them out to others. On what arable fields remained, declines in profits were also being alleviated nationally by the greater use of artificial fertilisers and weed-killers, which were becoming more available as by-products of the metallurgical, gas and chemical industries. Grassland was also being improved to increase the proportion of the more nutritious grasses and thus enhance milk yields and the growth-rates of cattle. Both started to have impacts on the distribution of wild flowers and grasses, exacerbating the effect of the withdrawal of sheep-grazing. At the same time, rolling and autumn cultivation were introduced to control insect pests in the soil, exposing them to birds like rooks and lapwings, who thereby benefited.

Before the second world war these changes were slow to occur and most local farmers cherished traditional ways. Mr Bellingham of Hatches Farm was still walking flocks of sheep along the old road to Aylesbury (according to one of the recollections in Holy Trinity Church 1999). Hillcrest Dairy operated from Hatches Farm through the second world war and delivered locally using a Morris 8 van. Massingham (1940) describes how the old craftsmanship was still valued at "Lisley’s Farm" (Sladmore), Great Kingshill, where he saw thatched hayricks that he regarded as masterpieces of the art:

… all the rounded ones have each a “dolly” at the apex, a stylized crown of plaited straw surmounted by a tuft of wheat ears and coiled at the base with a woven straw-band which, as Mr. Lisley told me himself, is 30 feet long.

Similar ricks were built elsewhere in the parish, too, as is shown in a photograph of Collings Hanger Farm about 1910. For thatching they were still using the old ladders that had curving side-pieces, broad at the base and narrow towards the top, that were also used for cherry-picking.

Other local industries

Economic opportunities in Prestwood outside farming and forestry continued to be scarce. Samuel Howard, still using a horse to turn the pug mill, continued his brickyard, living in the house called Kiln Lodge beside it. He supplied bricks for the Queensway Mersey Tunnel in 1934. (Some, however, bemoaned the "Chilterns brickfields which mar the scene and pollute the air" - Druce 1926.) At the beginning of the second world war Samuel Howard was forced to cease operation because the fires of the brick-kilns would have provided a guide to enemy aeroplanes seeking out Chequers. His son John re-opened the yard after the war in 1949, but it failed to thrive and closed in the 1950s. John since moved to Portsmouth.

Samuel Howard's brickyard, Honor End Lane, c1927. Horse harnessed

to the beam of a pugmill, which worked the clay prior to being place in the

moulds to make bricks.

Fancy brickwork and ironwork gate to Kiln Lodge 2006. Photo by Val Marshall.

The working of Denner Hill stone was abandoned at some time in the 1920s.

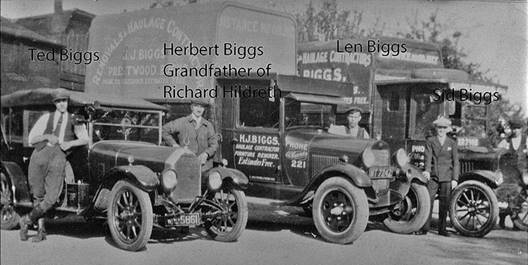

Members of the Hildreth family were still working as blacksmiths along Wycombe Road and at Blacksmith Lane in the 1950s, and there was another blacksmith below Hotley Bottom on the Rignall Road (he also sold drinks in the 1930s), but this trade would survive very little longer. (The forge at Hotley Bottom, however, still produces decorative ironwork to this day.)

Hildreth's Forge c1901: fixing a hot steel rim on a cartwheel to shrink into place on cooling