Part III Prestwood After 1851

9 The Enclosures and Beyond: 1850-1900

… these Justices and Gentlemen have enclosed the Fields and the cause of laying down the flails The Devil will Whip them into Helltails.

From a poster at Bicester 1800, quoted in Hay, Linebaugh, Rule, Thompson & Winslow “Albion’s Fatal Tree”

Those fenceless fields the sons of wealth divide,

And even the bare-worn common is denied.

Oliver Goldsmith "The Deserted Village"

In some ways the next fifty years was a relatively stable period for Prestwood. A number of the houses in 1850 were of recent origin, representing a moderate expansion of population in the 1830s and 1840s, and this modest expansion continued during the rest of the C19th, with about half as many households again in 1900 as in 1850 (i.e. an increase of just over one house per year). The lives and work of the people, too, changed very little. For an era of supposedly major progress, the Victorian age brought little benefit to the rural farm-worker. Admittedly, some diseases like cholera and typhus were almost eradicated, and typhoid fever (an intestinal disease unrelated to typhus) much reduced, but medicine was still primitive and largely unavailable to the ordinary person. While Prestwood did not suffer from the growing overcrowding of the cities and its associated social ills, infant mortality rates were just as bad in 1900 as they were in 1850. About 20% of infants aged 0-9 died between each decennial census: the death of young child was a normal event, experienced by all but the luckiest families. Even the farmers had to cope with continuing plagues among their animals – foot-and-mouth raged widely, “cattle plague (rinderpest) and pleuro-pneumonia” broke out several times (Wilson 2002). Likewise the “golden age” of capitalism was less visible in this rural backwater than in the large towns and cities where industry flourished, with one exception. This exception was only the culmination of change that had started decades earlier, but it would eventually influence the environmental character of the area in a major way. This was the demise of virtually all the common land.

The Loss of the Commons

"The Mores"

by John Clare c1831

Far spread the moorey ground a level scene

Bespread with rush and one eternal green

That never felt the rage of blundering plough

Though centurys wreathed spring's blossoms on its brow

Still meeting plains that stretched them far away

In uncheckt shadows of green, brown, and grey

Unbounded freedom ruled the wandering scene

Nor fence of ownership crept in between

To hide the prospect of the following eye

Its only bondage was the circling sky

One mighty flat undwarfed by bush and tree

Spread its faint shadow of immensity

And lost itself, which seemed to eke its bounds

In the blue mist the horizon's edge surrounds

Now this sweet vision of my boyish hours

Free as spring clouds and wild as summer flowers

Is faded all - a hope that blossomed free,

And hath been once, no more shall ever be

Inclosure came and trampled on the grave

Of labour's rights and left the poor a slave

And memory's pride ere want to wealth did bow

Is both the shadow and the substance now

The sheep and cows were free to range as then

Where change might prompt nor felt the bonds of men

Cows went and came, with evening morn and night,

To the wild pasture as their common right

And sheep, unfolded with the rising sun

Heard the swains shout and felt their freedom won

Tracked the red fallow field and heath and plain

Then met the brook and drank and roamed again

The brook that dribbled on as clear as glass

Beneath the roots they hid among the grass

While the glad shepherd traced their tracks along

Free as the lark and happy as her song

But now all's fled and flats of many a dye

That seemed to lengthen with the following eye

Moors, loosing from the sight, far, smooth, and blea

Where swoopt the plover in its pleasure free

Are vanished now with commons wild and gay

As poet's visions of life's early day

Mulberry-bushes* where the boy would run

To fill his hands with fruit are grubbed and done

And hedgrow-briars - flower-lovers overjoyed

Came and got flower-pots - these are all destroyed

And sky-bound mores in mangled garbs are left

Like mighty giants of their limbs bereft

Fence now meets fence in owners' little bounds

Of field and meadow large as garden grounds

In little parcels little minds to please

With men and flocks imprisoned ill at ease

Each little path that led its pleasant way

As sweet as morning leading night astray

Where little flowers bloomed round a varied host

That travel felt delighted to be lost

Nor grudged the steps that he had ta'en as vain

When right roads traced his journeys and again -

Nay, on a broken tree he'd sit awhile

To see the mores and fields and meadows smile

Sometimes with cowslaps smothered - then all white

With daiseys - then the summer's splendid sight

Of cornfields crimson o'er the headache bloomd

Like splendid armys for the battle plumed

He gazed upon them with wild fancy's eye

As fallen landscapes from an evening sky

These paths are stopt - the rude philistine's thrall

Is laid upon them and destroyed them all

Each little tyrant with his little sign

Shows where man claims earth glows no more divine

But paths to freedom and to childhood dear

A board sticks up to notice 'no road here'

And on the tree with ivy overhung

The hated sign by vulgar taste is hung

As tho' the very birds should learn to know

When they go there they must no further go

Thus, with the poor, scared freedom bade goodbye

And much they feel it in the smothered sigh

And birds and trees and flowers without a name

All sighed when lawless law's enclosure came

And dreams of plunder in such rebel schemes

Have found too truly that they were but dreams.

* = blackberries

In 1850, 15% of the area of the parish was common land. By that time there had already been incursions into local commons, especially in the Kiln Common area and the north part of Prestwood Common, with the establishment of privately-owned enclosed fields and homesteads of dubious legality. During just five more years, however, beginning in 1851, virtually the whole of the rest of these commons (described in the deeds as “waste land” – economic-speak for “not producing a profit for an individual landowner”) were enclosed by a succession of orders of the Justices as agricultural land under private ownership. All that then remained of the common land at Prestwood and Great Kingshill were two ponds beside Honor End Lane (one of them the Sheepwash), two ‘recreation grounds’ (although these were not properly levelled as such until nearly the end of the century) and four allotments. On Denner Hill nothing was left at all. This was the final act in a wave of Parliamentary Enclosures that began elsewhere in England about 1760 and had already taken Kiln Common in the name of "improvement" - more economic-speak for "making profit for the few at the expense of the many". By 1870 one sixth of the area of England had been changed, through 4,000 acts of parliament, from common land to enclosure by what could well be described as legalised theft, providing no compensation for most cottagers' rights (Fairlie 2009). Even those with smallholdings ("encroachments") generally found the costs of complete enclosure disproportionate and were forced to sell out to larger landowners. While there were badly used commons that fitted Lloyd's condemnation (Ch. 7c, p.17), the main impetus for these enclosures was the need of current landowners to enlarge their holdings to maintain profitability and to be able to employ the latest techniques and innovations in farming methods, coupled with a more contentious desire on their part to reduce the independence of cottagers by making them totally reliant on wage-labour (articulated in moral terms as a denigration of lazy impoverished peasants "not inclined to work for wages") (Fairlie 2009). What was also seldom pointed out was that overstocking of commons was often by neighbouring landowners enlarging their holdings by stealth where they could not do so by purchase (the labouring cottager in any case had no means to enlarge his number of cows or goats).

While this raised the agricultural output of the area considerably and enabled farmers to make investments to increae productivity and take advantage of the expanding markets for food in the manufacturing communities, it concentrated resources into the hands of a relatively small number of wealthy landowners who had the capital to invest in this new land. The enclosures did not proceed without protest from local cottagers, culminating in rural riots in the 1830s in some areas of the country, although, as usually happens, “economic progress” won the day. There was an accompanying consolidation of farm ownership with the loss of the smallest farms. The local directories for the Great Missenden civil parish (which included something approaching a half of Prestwood parish residents) show a decline from 34 to 27 farmers from 1854 to 1864, and dropped to as few as 18 in 1877, only rising again in the 1890s, when there were 29 farmers in the parish at the end of the century. Importation of cheap wheat and wool was pressing on English agriculture, but those farmers who weathered the storm and bought up the holdings of the less successful, while holding down labourers’ wages, came out of it even better off.

Customary rights of the rural workers to the use of this common land – the cutting of gorse and brush as fuel, winter flailing of grassland, raising poultry, growing vegetables, grazing and watering animals – were suddenly lost. For families on meagre incomes this apparently minor loss was more serious than it might seem (Court 1962). The loss of their smallholdings was often the difference between survival and going under (Hammond & Hammond 1920). “ The labourers had to leave the land or starve ” (Wilson, 2002). According to Neeson (1993) an average cottager's cow provided a gallon of milk a day, earning the equivalent of half a full-time labourer's wage. An acre of gorse (derided by advocates of enclosure as worthless scrub) was worth 45 days' labour when cut and sold as fuel to bakers and operators of brick-kilns. Cottagers received no compensation for these losses, although Acts of Inclosure handsomely compensated those gentlemen who could claim manorial rights in the soil and trees, even though they had made no input to the improvement of the land. In the case of Denner Hill, Edward Grubb (who did not live locally) claimed compensation for rights in Denner Hill and Bryants Bottom commons, Denner Hill Coppice and Spring Coppice.

One improvement that did result from enclosure was the impetus it gave to improvement in the roads, as the new farmlands had to be more easily accessible, while the old commons tracks were treacherously rutted and pitted, often obstructed by scrub. Thus Rolls Lane, metalled where it came up Denner Hill from Stony Green, had continued along the crest of the hill all the way to Acrehill Wood as a muddy track, but after enclosure of the commons through which it passed, it was cleared to a width of 20 feet, the central 10 feet filled with broken flints to an average depth of 6 inches. Similarly the ancient tracks across Prestwood Common were laid with stones (providing some employment for labour), that along the northern edge eventually becoming Prestwood High Street.

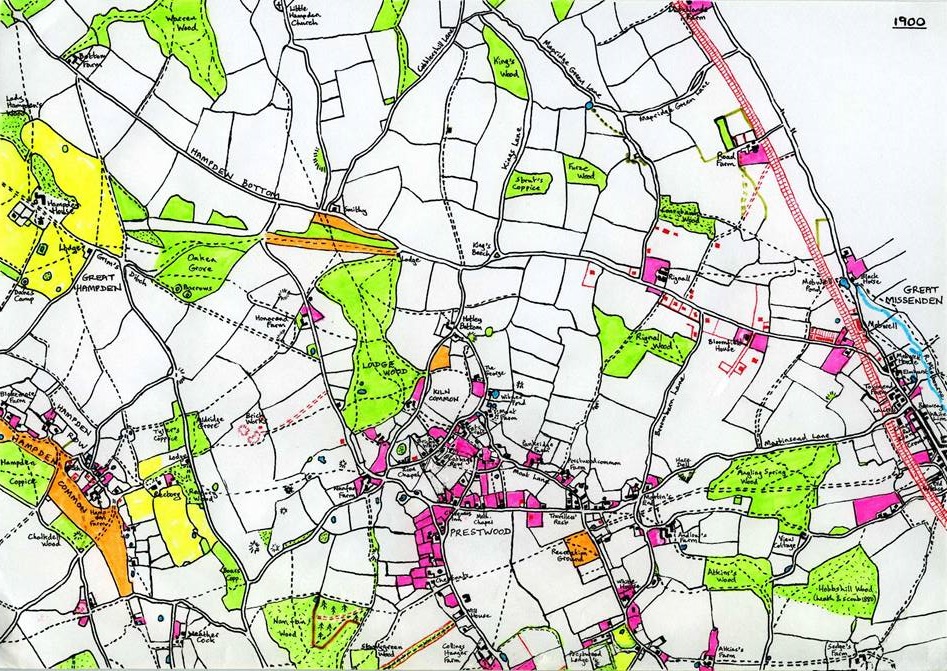

Map of North Prestwood Area in 1900

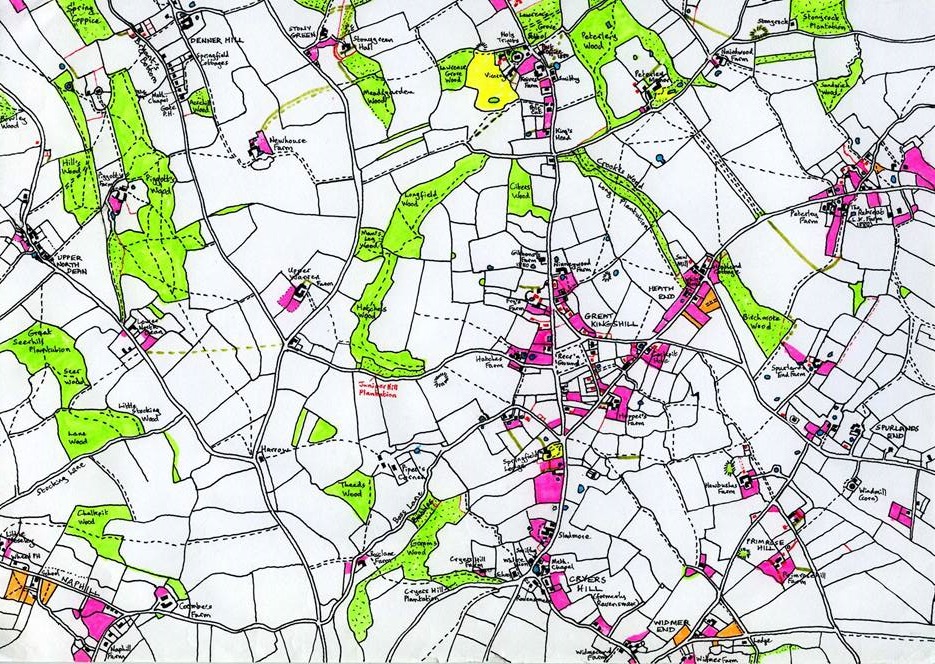

Map of South Prestwood Area in 1900

Population

The population of the ecclesiastical parish is difficult to determine precisely, because its boundaries were different from those of the civil parishes used in the census, and addresses in the earlier censuses were sometimes vague. Although the church parish included only part of Great Kingshill, it is impossible to know which of the households described as part of that hamlet were inside the parish. For populations, therefore, I have had to take the combined total for Prestwood, Great Kingshill and the other outlying clusters of houses like Bryant's Bottom. The number of occupied households, as best as can be ascertained, rose from about 190 in the two decades before 1860 to about 250 over the period 1861 to 1891, a rise of over 30% , after which it rose to 270 in the last decade of the century. The population of individuals varied in exactly the same way, as there was no change in the average of roughly 4.5 persons per household over that period. In 1861, 1,077 people of all ages were recorded by the census, this expanding to 1,189 by 1901, a 10% increase. Prestwood Parish therefore experienced two fairly rapid periods of growth, the first 1850-1860 consequent on the enclosures, and, after four decades of relative stability, the second 1890-1900, after a sudden surge in new building, particularly the development of the High Street in Prestwood and the expansion of Bryant's Bottom (from 2 houses in 1851 to 16 in 1901) and Great Kingshill. The number of households in Prestwood alone (omitting Great Kingshill and the outlying settlements), rose from 115 before 1861 to an average of 145 during 1861 to 1891, and then 155 by the end of the century. Prestwood therefore saw a slightly lower rate of increase in the last decade (7%) than the rest of the parish. The population of Prestwood had always been more dependent on agriculture than those of Great Kingshill and Bryant's Bottom, where woodland industries (and, to a small extent, stone-cutting) were more prevalent, so that Prestwood's fortunes waxed and waned with those of farming (see below).

Bryants Bottom nestles in the narrow valley between Denner Hill (left) and Piggots Hill (right). Seen from Spring Coppice Lane 2018

Chiltern Cottage (1870) was one of the first houses built along the new High Street replacing the traditional old flint cottages with houses made of brick.

The Roses (1891), another of the new houses on the High Street

The age distribution of this population did not vary significantly from 1851 to 1901, except for a slight increase in the numbers of persons aged over 60, which rose from 7% before 1881 to 10% in 1891 and 11% in 1901. This appears to reflect reductions in the birth-rate, with 29% of the population in 1851- 1881 having been born in the previous decade, 27% in 1891 and 25% in 1901, showing the beginnings of a general reduction in family sizes that may reflect a change in ideology from a laissez-faire policy of parenting to one where people were beginning to exercise some control.

Over two-thirds of the population of the parish had been born in that area throughout this time, the figure varying only between 69% and 73% between censuses, with no sign of any trend. Immigration from neighbouring parishes, and even Bucks generally, did not increase, but there were slightly more arriving from further afield, rising from 7% on average from 1851 to 1881, to 9% in 1891 and 10% in 1901.

These were the first tentative signs of the impact of changes in agriculture, the rise of industrial towns, and a general improvement in travel enabling greater mobility, that together would make a considerable difference in the next century. But for the moment, Prestwood > had changed remarkably little socially over fifty years, despite the underlying economic changes that we shall look at next. In some ways, indeed, the parish had become more stable in population than ever, because the role of migrant agricultural labour was declining.

Of families represented in the censuses of 1841 to 1871, an average of roughtly 60% were still in the parish ten years later; whereas 70% of families represented in the parish in 1881 and 1891 were still there a decade on. There was, however, much less domination of the population by a few families. In 1841 and 1851, 13% of all households had the surnames of Mason or Nash (24 to 25 households), dropping to 9% in 1861 (23), 6.5% in 1871-81 (17), 5% in 1891 (14) and 4% in 1901 (12). Other family names common in the parish at different times were Saunders (8 to 10 households 1861-71), Smith (10 in 1871 and 4 to 6 in subsequent years), Taylor (9 in 1881-91 and 4 in 1901) and Wright (7 in 1891, 4 in 1901). (These statistics only represent descent in the male line - daughters of these same families were also represented under different married names, but they cannot be systematically traced. The figures therefore under-estimate the full extent of the persistence of families in the parish, although this does not affect the annual comparisons.)

Choice of personal names also became progressively less conservative. For each census we can look at the given names of those born in the preceding decade. In 1841 over two-thirds (68%) of boys aged under ten were called either William (78) or John (55). The same names dominated in the next decade, but together they only accounted for 60%, a figure equalled in 1851-61, except that John had dropped to third place and George had replaced it. William and George dominated for the rest of the century, but together they accounted for a smaller and smaller percentage, until in 1891-1901 they represented only 38% of all new names. The same picture is shown by girls' names, where Mary and Ann dominated during 1831-51, accounting for over 60% of the total, followed by Mary and Sarah 1851-71 (about 54%), Mary and Ann again 1871-91 (44%), and finally Mary and Sarah 1891-1901 (but just 32% of all new names). Apart from these common names (to which could be added Thomas, James, Charles and Frederick for boys, and Elizabeth for girls), children in the more religious families were often given biblical names such as Boaz, Job, Ezekiel and Hephzibah. Fashion sometimes played a part. The most dramatic instance of this was the rise of "Albert", not seen before 1841, occurring twice each in the next two decades, and then suddenly 15 times 1861-71, 6 times 1871-81, 15 times 1881-91, 33 times 1891-1901, and 9 times 1891-1901. This can hardly be ascribed other than to the popularity of Queen Victoria's royal consort Prince Albert, whom she married in 1840 and who died suddenly in 1861. His death was transmitted across the country via the ringing of church bells and it was seen as a national calamity, as well as a loss from which his widow never fully recovered. Public mourning took on an intensity only witnessed over a century later with the death of Princess Diana. Prestwood may have been a rural backwater, but it was clearly not unaffected by these events. Interestingly, Victoria was never used as a girl's name in the parish during the nineteenth century (except once as a middle name): perhaps it was too presumptuous to name a child after the Queen.

Economic Activity

1. Farming

Some of the enclosures were large – the whole north-western quarter of Prestwood Common became the huge Sixty Acre Field (a name since enshrined in the road built across the middle of it around 1960 and now the centre of a large housing estate). Larger fields provided greater opportunity for mechanisation, such as horse-drawn ploughs and mowing machines. Although, for most of the latter half of the 19th century, farming methods changed little and remained highly labour-intensive compared with today, this mechanisation had a direct effect on numbers of labourers employed in agriculture. In 1851 40% of household heads were agricultural labourers, in 1861 38%, 1871 32%, 1881 29%, 1891 19%, and by 1901 only 11%. Other local labouring opportunities (carriers, firewood-cutting, brick-works, road-making, latterly the railways) were only small in number and, although they increased over time, they nowhere near made up for the loss of agricultural work (from 1851 to 1901 the proportion of household heads in non-agricultural labour rose from 4% to 17%). As a result, those in unskilled work of all kinds fell from 44% to 28%. The loss was made up to a small extent by the more entrepreneurial of the labourers renting smallholdings and setting themselves up as independent small farmers with a few animals or vegetable crops, orchards or poultry (see below), sometimes supplementing meagre profits by running a beerhouse. Apart from that there was only one place for the surplus labour to go and that was to the growing towns and cities, especially to the mill towns up north, leaving Prestwood altogether (a movement that was not reversed until the middle of the 20th century and later, when there was migration out of the crowded cities to dormitory towns). In some cases this emigration took the extreme form of leaving for one of the growing countries abroad, and this half-century was a peak one for emigration to the United States, Canada, Australia and New Zealand (often bolstered by land grants in the case of America and other subsidies from the receiving countries, which essentially made travel free, albeit still arduous). By 1901, for the first time, there were more labouring jobs outside agriculture than in it, and a tipping point had been reached in rural communities, no longer dominated by a majority of agricultural labouring cottagers.

The C19th was the age of "improvement" with all sorts of innovations, sensible and otherwise, promoted and experimented with. Many new measures involved economies of scale, in which enclosure and the resulting large fields, or the destruction of hedgerows to the same effect, were integral to success. New designs of machinery such as seed-drills, threshing machines and steam-ploughs also enabled the more cost-efficient use of labour. There was great optimism at the time among the larger farmers that profits would burgeon, but these were actually more dependent on worldwide economics and the effects of wars and famines. Many of the new large farms proved much less profitable than had been expected, especially given the inherent limitations of the Chiltern geology and topography. Already, by the end of the century, some of these new agricultural enclosures were being sold off for building land, as they were never going to be sufficiently productive. The most level-headed and scientific of the farmers however, could make a go of it and gradually tended to dominate the region. In Prestwood the most successful farming dynasty was that descended from the Davis's on Denner Hill. Their steady progress continued massively into the following century, coupled with the progressively-minded Stevenses. Farmers are generally regarded as conservative by nature, but it is those with an open mind towards change and the ability to move with external economic exigencies who survived in the long term.

There were two major foreign events that had an effect on agriculture in this half-century. They were the Crimean War (1853-55) and the Franco-German War (1872-73). War was profitable for those who bred horses for the cavalry and grew corn for their sustenance. At the same time surplus labour might well be drafted into the army, often leaving local manpower shortages. The combination of increased demand for agricultural produce and limited labour supply kept labouring wages relatively high (although still not competitive with those offered by new urban industries like furniture-making). According to Handford (2011) the average farm worker's wage rose steadily from 9s6d a week in 1824 to 14s5d in 1898. The effect of these wars was to buttress farming from the full effects of changing world economics, which would be more fully felt in the next century.

Farming methods were self-sustaining, a mixture of animal husbandry on pasture land and arable cultivation, which were closely interlinked. Dung from the pastures was used to fertilise ploughed land. Crop rotation ensured that soils did not become exhausted, essential before the invention of artificial fertilisers. The stalks of wheat remaining after harvest (longer than today’s varieties) were used for thatching. Old hedgerows continued to be managed in the traditional way by laying, and new hawthorn hedgerows were created to mark the divisions between the plots of land. Keen (1980) records that by the end of the century these hedges had grown sufficiently tall and thick to muffle the church bell at the other side of the former common! Beyond the commons, too, fields were amalgamated, reducing the patchwork quilt effect of the narrow strips that had survived in places from medieval times.

All three of the main cereal crops were grown in this area: wheat, oats and barley. They were sown after spring ploughing. The wheat was grown for flour and bread-making, having been watered with a copper sulphate solution to prevent fungal diseases like smut. There was a mill in Great Missenden for grinding the corn. Oats were primarily animal feed, especially for horses. Barley, particularly suited to the chalk fields, was grown for the breweries situated in the surrounding communities of Great Missenden, Amersham and High Wycombe.

The cereal crops were under-sown with grasses and leguminous plants, which helped to fix nitrogen in the soil and preserve its fertility. After harvesting the corn in the late summer, it was piled in stooks to dry and the under-sown crops allowed to develop to be grazed by animal stocks or, in the case of grass, cut for hay the following summer. This was followed by another sowing of cereals the next spring, after the harvest of which the land would be ploughed and harrowed in preparation for the sowing in the following spring of root crops: mangolds, turnips and swedes. These again were grown for animal fodder, and animals like cows and sheep were taken from their summer pastures to graze the turnips from autumn to the end of the year and thereafter the swedes until April. Between these two crops there was often an autumn-sown “catch crop” of vetch, rye or barley, also used as forage, and serving to further fix nitrogen as well as controlling the growth of weeds. The root crops, while providing animal food, also served as a “cleaning crop”, regular hand hoeing between the rows serving to prevent weeds getting out of hand. Farmyard manure was also applied at this stage to promote the growth of the crops, as well as contributing to the fertility of the soil in the subsequent year when cereals would again be grown. (This account owes much to Stoate, 1995, supplementing local information.) While mechanisation and artificial fertilisers were beginning to change farming radically in some parts of the country, the size and topography of local farms made this less easy, and major mechanisation occurred only after 1900.

Animal husbandry consisted mostly of cattle, pigs and sheep. There had always been someone who dealt with the slaughter of these animals, but it was not a specialised role until the late 1870s when Alfred Stevens expanded his business to start employing a slaughterman. By 1901 there were four people employed in this way, and the business continued to expand even more in the following century. There were still four people employed as shepherds in 1901, so that there seems to have been no decline in the number of flocks kept in the parish, although sheep-rearing was to dwindle to virtually nil in the following century. All these flocks were, however, relatively small.

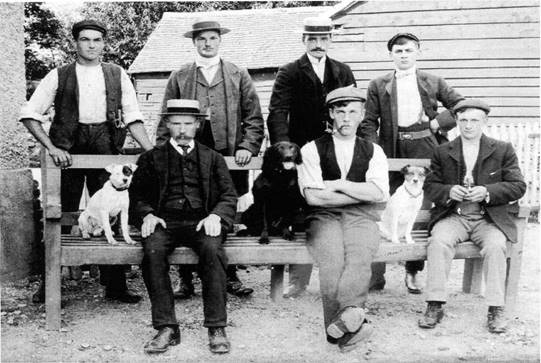

The role of the agricultural labourer was integral to all these activities, and sometimes, at times of peak demand (fruit-picking, corn harvest, hay-making) their families would be drafted in too (although women and children were only paid a pittance). Farm workers had to be able plough and sow, tend crops, feed and care for farm animals, milk cows, herd and shear sheep, trim and lay hedges, maintain farm buildings, fences, gates, tracks and ponds, harvest with a scythe (which replaced the sickle around 1850), construct sheaves and hay-ricks, and thresh corn. It was not a simple job and involved a large range of skills picked up from older co-workers (especially their own fathers) and experience. It was exacting work, long (most daylight hours), poorly paid, but healthy in the fresh air. Rural workers had far higher life expectancies than their counterparts in the cities. It reminds us that the countryside does not maintain itself and in the late C19th it would have been full of people working on these various tasks, not the quiet empty experience we have today when crossing the fields. As the use of machinery replaced much labour, this all began to change, but the full effects of that would wait until the years after 1900.

The essence of the local countryside in 1875 was captured by Robert Louis Stevenson, who took a walk that autumn from High Wycombe to Tring. At first he was struck by the quietness of the roads and all he heard was overhead " a carolling of larks " such that he christened it "The Country of Larks". But eventually, he continues, " I left the road and struck across country. It was rather a revelation to pass from between the hedgerows and find quite a bustle on the other side, a great coming and going of school-children upon by-paths, and, in every second field, lusty horses and stout country-folk a-ploughing. " From here he passed through a wood (which might well have been Angling Spring) and descended to Great Missenden. Later, between Wendover and Tring, he describes how " The fields were busy with people ploughing and sowing; every here and there a jug of ale stood in the angle of the hedge, and I could see many a team wait smoking in the furrow as ploughman or sower stepped aside for a moment to take a draught. Over all the brown ploughlands, and under all the leafless hedgerows, there was a stout piece of labour abroad, and, as it were, a spirit of picnic. The horses smoked and the men laboured and shouted and drank in the sharp autumn morning; so that one had a strong effect of large, open-air existence. "

Woodland As stated at the end of Chapter 3, the old woodlands were already much reduced by the beginning of the C19th, although the process continued piecemeal. Woodland on Denner Hill was reduced to one small fragment, Acrehill Wood. The line of woods along the valley followed by what is now Hampden Road was broken up by fields. The whole of the woodland on the west side of the road was felled, and, on the east side, virtually all of that north of Nanfan Wood disappeared and a large gap was created at Stony Green for the new Stonygreen Hall (see below). Small plantations of conifers near Heath End and Stony Green were also clear-felled and replaced by pastureland. Much remained, however, and the furniture industry in Wycombe still commanded the services of those turning chair-legs, like the Gurneys, of whom Victor, born in 1905 (died 1987 in Lincolnshire), was to become one of the last of the working ‘bodgers’ in Prestwood. (The term "bodger" was a local term for a turner of chair-legs used in the Wycombe area only from the late C19th onwards; in the censuses of this time the term is never used, such workers being called "(wood) turners". While they worked in roughly-made camps in the woods during the day, they were not itinerant workers as some have inferred, and walked home to their cottages every evening. They were in fact skilled manual workers and long-term local residents. Although the origin of the dialect term is obscure, it has nothing to do with "botched" or unskilled work.)In 1851 13% of household heads worked in woodland industries of some kind - carpenters, joiners, cart saddle-tree makers, sawyers and turners. By 1861 this was 17%, 1871 20%, 1881 19%, and by 1891 26%, although thereafter a decline began (back down to 17% in 1901) that would would see these industries decrease in importance through the C20 th . The largest rise was among the "turners", who increased from 2% of household heads in 1851 to 14% in 1891, falling back to 6% ten years later. The peak of the timber-based economy therefore occurred about 1890. These jobs were stimulated by the growth of the furniture industry in High Wycombe, which specialised particularly in chairs, for which the bodgers supplied the legs and other components on commission. The rise in woodland industry, however, failed to compensate for the loss of farming jobs, and in any case agricultural families rarely moved into forestry employment.

A few woodsmen set themselves up as timber merchants, serving local demand, and this at least created some independence from the urban firms and supplied employment for sawyers, woodcutters and carters. There were three local timber dealers in 1901.

Orchards

Another diversification from farming was the growth of fruit production. In 1850 there were many orchards (all farms and some pubs - eg Polecat, Red Lion - had one), but they were small and intended mostly for domestic consumption and local sale of surplus. Fruit goes off quickly and there was no means of reaching a wider circle of consumers. It was the arrival of the railway from London to Great Missenden in 1892 that for the first time provided a rapid means of transport to get fresh fruit to a much larger population, supplemented by the Midlands in 1899 when a rail link to that region was established via Aylesbury.

By 1900 orchards were well established over much of the parish and many of them were very large. Most of the Prestwood and Great Kingshill settlements themselves were surrounded by orchards. They occurred also along the Wycombe road south of the church, at Heath End, on Denner Hill, near most of the farms and large houses like Peterley Manor, Prestwood Lodge and the White House. Cherries were the local speciality in Prestwood and Hughenden, but there were also plums, greengages, damsons, apples and pears, including large apple orchards in the Kingshill-Holmer Green area. Springtime would have been a glory of pink-and-white-blossoming trees and the buzz of bees:

Loveliest of trees, the cherry nowIs hung with bloom along the bough,

And stands about the woodland ride

Wearing white for Eastertide.

(AE Housman, from “A Shropshire Lad”.)

Summer to autumn was a time of seasonal employment for fruit-pickers. Tall cherry trees, some forty feet high, were accessed by long narrow curving ladders (up to 60 rungs), some of which survive (such as that on display at the Chiltern Open Air Museum). They look decidedly precarious. An experienced cherry-picker, moreover, would be able to balance on the ladder so as to leave both hands free for picking, by hooking one leg between the rungs and catching a lower rung with the foot. These ladders were made in Holmer Green, using pine trunks split in half as the sides. The migrant travellers were generally esteemed the best pickers, and they arrived in their caravans around the end of June. One of their campsites was beside the Bryants Bottom Road near the Gate pub; they also camped to the east of Prestwood above Great Missenden (Hobbshill Lane) and towards Cobblershill (Maples Green) in similar open areas beside green lanes. Whatever their origin these transient groups were all called "gypsies" by the resident population, and "Gypsy Lane" is still an alternative name for Hobbshill Lane, and one branch of Mapridge Green Lane near Cobblershill. Their visits continued well into the C20th and outside the harvest seasons they often gained employment removing stones from cultivated fields. They also cut hazel sticks to make pegs to sell locally and cooked hedgehogs and rabbits (memories of Mrs Grace Higgin, née Tilbury, interviewed by Marilyn Fletcher in 2006, when she lived in Whitefield Lane, Great Missenden). Other cherry-pickers came from the cities (Midlands, London) during the annual fortnight summer holiday when all factories closed down. Employment by the fruit industry was too seasonal (bird-scarers in the spring and fruit pickers in short periods of the summer and autumn) and not sufficient to maintain settled cottagers unless they had the means to buy land and run their own orchards. The most frequent local variety, Prestwood Black, was used for making dyes to colour cloth, being sent to mills in Oxford for this purpose.

PoultryLarge-scale poultry farming began in 1875 when the Davis family started keeping pheasants on Denner Hill. “[ W]icker baskets filled with pheasants’ eggs (each egg hand-wrapped in woodwool )” were sent by train to sporting estates all across England and even in Scotland. Familiar to everyone today after over a century of “escapes”, these exotic Asian birds “strutting the fields” were a strange experience to residents at this time (Davis 2004). In 1899 Arthur Davis married Kate Purssell, daughter of William Purssell, who had himself kept pheasants at neighbouring Little Hampden. Other pheasant keepers in 1900 were George Saunders (1841) at Peterley, Charles Hannell (1859) on the east side of Prestwood Common, Alfred Bedford (1873) at Knives Farm (his father Daniel being the principal keeper), William Ward (1856) and his son Ralph (1885) at Kiln Common, and Alfred Chandler (1867) from Wendover at Martinsend Lane. In 1894 Alfred Tompkins (1871) purchased the defunct Golden Ball public house to start keeping a few hens, acting as a middleman for numerous other poultry-keepers. By 1900, there was also a poultry farm at Prestwood Lodge, run by Henry Way (1863) from Gloucestershire, and two in Great Kingshill - Ernest Brown (1869) moving from West Wycombe and William Simmonds (1841) at the Royal Oak. (Many of these were young men more able to adapt to the new entrepreneurial opportunities of the times; others branched out from other trades like inn-keeping.) This line of agriculture would burgeon in the following century, building on what had until then been, like fruit growing, effectively a cottage industry – a few hens in the back garden. While some of these were one-man operations, the larger ones offered employment for other local people.

Brickmaking

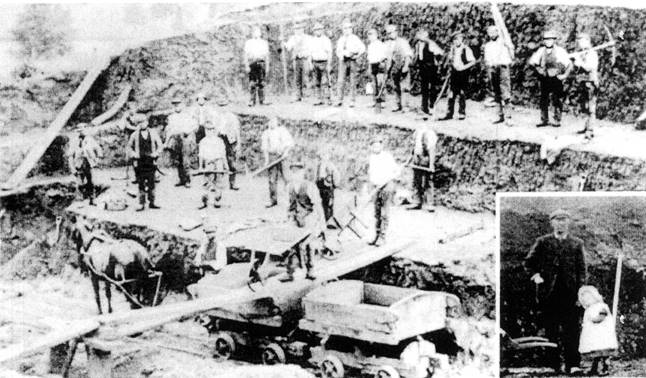

One activity that eventually took an upturn was the brickmaking industry, in support of the building boom in the region. Avery’s declining yard was revived by Solomon Groom in 1876, as an addition to his shop business, and he lived beside it in Brick Kiln House until he died in 1907. The yard was employing at least 25 by the end of the century, including his brother Henry (1858) and Benjamin Howard (1880), thus making a considerable contribution to the local economy.

Elisha Essex from Moat Farm set up another small yard with just one kiln, also at Kiln Common, in the late 1860s, but this was no longer operating by 1880. Finally, a large new brickyard employing seven men was established by Samuel Howard in a new area north-west of Nanfans. Samuel was born in Surrey 1874 but was later brought up in the little village of Bellingdon near Chesham, where his father ran a brickyard. He may have worked for Solomon Groom initially (as his brother Benjamin was still doing in 1900), before setting up on his own, as both he and his brother lived in Chequers Lane in 1898, near Groom’s yard. Shortly thereafter he got married and set up his own brickyard off Honor End Lane, erecting Kiln Lodge there as his residence. Fancy brickwork as part of the entrance to the Lodge garden survives to this day.

Digging clay at Groom's brickyard, 1890s. Inset: Solomon Groom & grand-daughter Cissie

Stone-cutting

The small industry centred on Denner Hill continued through the rest of the C19th, but was never sufficient to provide employment for more than seven parish men and a few others at its peak in 1881, declining to five men resident in the parish by 1901. Stones were also dug from pits on the west side of Prestwood Common (corner of Sixty Acres and Wycombe Roads) and other places.

Women's work

Major changes were also evident in women’s work. A lace-making machine had already been invented in 1820. Originally the lace it produced (Nottingham lace) was poor and could not rival that of the cottage industries, whose products were in demand even from royalty. By 1875, however, the machinery had been improved and good lace could be produced much faster and more cheaply in urban factories. The rural cottage industry was no more. In 1851, 151 women and girls in the parish were employed in lacemaking, in 1861 142, in 1871 207, in 1881 85, 1891 19, and in 1901 just fifteen. Straw-plaiting grew slightly in importance to a peak in 1871-81 (when around 30 parish women were so employed) but had disappeared completely by 1901, unable to compete with cheap imports of plaits from China and Italy. This work may have been ill-paid and arduous, but it at least provided an important supplement to household incomes, so that its loss further disadvantaged the poorer cottagers. Women turned to other occupations - laundry, dressmaking, beadwork, nursing - engaging around 60 women in the last decades of the century (20 in beadwork), but none were of sufficient extent to make up for the loss of lacemaking. As always, a few of the younger women, mostly teenagers, found work as servants, and these posts increased from around 30 1851-1871 to around 40 1881-1901, but this in no way made up for the general loss of work.

Children's work

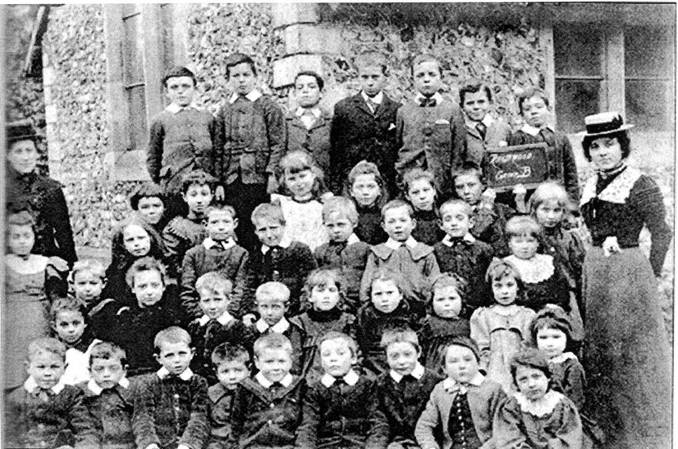

During this half-century school was only part-time and children were usually gainfully employed (for mere pennies) in haymaking, harvesting, fruit-picking, removing stones from fields, and bird-scaring in orchards. Girls were also instructed in straw plaiting and beadwork. From the establishment of the school at the parish church in 1850, children up to the age of 13 were able to obtain a rudimentary education, although ability to take advantage of this opportunity was dependent on the economic self-sufficiency of their families, and fluctuated seasonally according to the demands of farming. Holmes (2010) calculated that in 1851 less than a third of eligible children attended the new school, but this increased to nearly three-quarters by 1891.

Trades

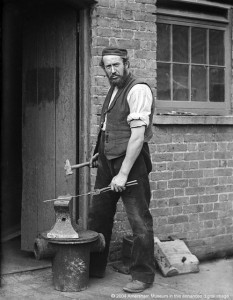

Prestwood remained largely an agricultural and woodworking community with relatively few facilities compared with the larger villages in the valleys. We have seen how, apart from the beerhouses, the other commercial enterprises present in the parish around 1850 were basic ones like grocers, shoemakers, bakers, wheelwrights, and blacksmiths. Most of these employed only family members. In nearby Great Missenden at the same time there was a much wider variety of trades and businesses, including drapers, saddlers, corn dealers, land agents, watchmaker, builders, tailors, plait merchant, plumber, chemist, ironmongers, doctor, confectioner, weaver, brewer, tinplate worker, basket manufacturer, straw bonnet manufacturers, dressmaker, coach proprietor, and post office.

Demand for these basic services would have varied little over the half-century. In 1901 in Prestwood parish there were still four blacksmiths, three shoemakers, three bakers, and two shops (a general dealer's and a confectionery). There was also one coal merchant, a stonemason, and a builder.

The increase in new building towards the end of century gave employment to a few bricklayers, painters, a plumber and other building tradesmen, while road improvements and the building of the railway to Great Missenden and beyond in the 1890s also saw more people employed as navvies.

The Leisured ClassesWhile the numbers of propertied people in the Directories for Great Missenden (described as “gentry” or later as “private residents”) steadily increased from 12 in 1864 to 39 in 1903, there was little expansion in Prestwood, which remained largely a community of labourers and woodworkers. The facilities in Great Missenden and its sheltered valley situation were more attractive to the well-to-do than the cooler, wetter and socially more primitive hilltop village. There were eight people described as having "independent means" in the 1901 census, the same as in 1881, and only two more than in 1861-71. Similarly, white collar roles were very limited; apart from the vicar and schoolmaster, in 1861 there was a registrar of births and deaths, Thomas Ward (1828), resident in one of the church buildings which also acted as a post office, of which he had been postmaster since 1858 (see below for more on the local post office). There was also a police constable stationed in Great Kingshill (George Page, just 26-years-old at the time). In 1871 there was also a barrister and magistrate living in Great Kingshill, although being 71-years-old he was probably mainly retired. By 1900 there was neither registrar nor policeman in the parish.

Stonygreen Hall

During the fifty years to 1900 only one gentrified house was to be built in Prestwood. This was Stonygreen Hall, erected in 1871, just above the isolated Stony Green cottages, with an impressive view across the valley to Denner Hill and with mature woodlands around. The owners, however, changed regularly. In 1881 this was the residence of 63-year-old Charles Townsend, a farmer from Witney , with his wife Matilda, a 17-year-old grandson helping with the farm, and a servant girl from Bledlow. They worked 120 acres and employed 6 labourers. They also employed a gamekeeper, Henry Short from Hampshire (but born in Dorset) with his German wife Zelie. Their son Ambrose (15) worked as stable-boy on the farm. In 1891 the Macfarlanes were in residence at the Hall with a housekeeper and a housemaid, but the farm was now occupied and run by 23-year-old Ebenezer Grange, newly arrived from Bledlow with a wife and son. By 1901 the Williams family had been in occupation for a couple of years, the wife from Jersey, with four servants (cook, parlourmaid, nurse and between-maid). None of these employees were from the local area.

Nearly a kilometre of new road was built from the old Wycombe road, starting from beside the Mill House, just to serve this new residence, with an avenue of trees planted regularly the whole way. Perhaps it was its isolation that encouraged stories such as the ghost of a lady galloping round the Hall on a white horse, head in hands; others have told of hearing a Roman soldier marching by Stony Green in hobnail boots, and of a jilted lady who walks up the road towards Great Hampden Church in a cloak (Nanton 1987).

Stonygreen Hall (at top) above Stony Green

Prestwood Lodge

There was some attempt to create the fashionable parklands of the Victorian age, of rolling grass and exotic trees, although here on a small scale. Tree plantings occurred, for instance, at Peterley Manor and Prestwood Lodge. At the latter a new drive for carriages was created from the new Nairdwood Lane, laid down when the arm of common-land, Peterley Common, on the east boundary of the house was converted into fields, preventing one just driving across the common to the Lodge. The new drive came off the Lane just north of Church Path, and curved through lawns and trees to finish in front of the house, which overlooked a large pond. One of the black-painted carved wooden gateposts that flanked the entrance to the drive was revealed by scrub-clearance in the late C20th, but this now seems to have disappeared. Peterley Lodge was in 1871-91 the residence of Emily Watson (born in Somerset), who in 1851 had been at Chestnut Farm with her husband James the spirit merchant. She had come back to Prestwood after moving to her London house on her husband's death. She had her own independent income and in 1871 kept a servant, cook, gardener, and dairywoman, the last three all members of the Hannell family who resided in a cottage by the Lodge. The Hannells remained in her employ until she died in 1895, when the house and grounds were taken over by Henry Way, a poultry farmer, who had previously lived in Gerrards Cross and before that in the United States, although he had been born in Gloucestershire.

Prestwood Lodge early C20th(when the original flint-built house had gained a 3-storey extension and conservatory)

Holy Trinity Church and Prestwood Park

The largest expanse of trees, however, was created by Re vd. Thomas Evetts on the glebelands behind the church, where the old pasture was planted with a scattering of foreign limes, turkey oaks, horse chestnuts, pine, and wellingtonia, as well as native beech. At its northern end he planted a speciality of the age, a Lucombe oak, a hybrid of turkey and cork oak that had first been propagated at Lucombe in Devon in 1762 and was commonly planted in the south of England in the ensuing century. His “pleasure grounds” (Keen, 1998a), part of which subsequently became known as Prestwood Park, were open to the public for picnics and festive events, such as the annual commemoration of the church’s consecration and the Harvest Festival introduced in 1857. They were also used by Evetts and his friends for their favourite sport of shooting game. A track that in 1850 had traversed this field from the south to the chalk-pit at the north end, and then continued down the eastern side of the field to the Polecat, was now diverted west so as to skirt the southern edge of the park and head directly towards the Polecat. As part of the glebelands Evetts was also in charge of Knives Farm, on whose land the church had been founded. He installed a bailiff Daniel Stadhams there.

Evetts was still curate at Holy Trinity in 1861, when he and his wife Elizabeth, still only 40 and 36 years old, having married at Headington, Oxford, in 1844, now had eight children, aged 7 months to 14 years. The servants had largely changed, as is the nature of such posts that mostly employ young people in their mid-teens and early twenties, except that local girl Elizabeth Redrup (25) was still employed, having now risen to "lady's maid". Her younger brother John (18) had also been recruited as a footman. Five of the nine servants had been born elsewhere, but two other local people were now employed as kitchen maid (Susannah Janes) and nursemaid (Martha Pearce). In 1851 Evetts's widowed mother was living with him, but she died in 1857 and he dedicated a stained-glass window in the church to her memory depicting "entombment and resurrection" (made by F.W.Oliphant).

Evetts left Prestwood in 1864, although in 1871 his son Basil Thomas Alfred, then 13, was a pupil at Revd. Arthur Hussey's school at Peterley Manor. In 1881 he graduated from Trinity College, Oxford, like his father, and became a historian, an authority on the Copts (Christian descendants of the ancient Egyptians). He wrote several books about the Coptic Church published between 1888 and 1915, including translations of Coptic works from the original Arabic. He died as a single man in 1919.

In 1864 Evetts was briefly succeeded by Revd. William Wood, but in 1866 the curacy devolved to Revd. William Thorley Gignac Hunt, a native of Bath, educated at Christ Church, Oxford 1856-62, who had previously been vicar at Dinton and Princes Risborough. He had married Mary Eliza Burgess in 1862, the daughter of Revd. William Joshua Burgess, who had held the incumbency of various parishes around Prestwood - including Sarratt, Great Missenden, Aston Clinton, and Lacey Green.

Revd. Hunt moved on in 1871, to be succeeded by John William Boyd (1871-75), who went on to become Master of Magdalen College School, Brackley in 1879.

He was followed by Harry Morland Wells, then just 34 years old, who held the post for a more substantial time, until 1892. He employed seven servants at the Vicarage, but none were from Buckinghamshire. Revd. Wells was the son of the Hon. Frederick Octavius Wells, a Chief Justice in the Bengal Civil Service. His brother was Admiral Sir Richard Wells, while a sister Mary Julia married the Rt.Hon. Sir Thomas Frederick Halsey, 1st Baronet; so he was remarkably well connected. Of his own sons living at home at the time of the 1881 Prestwood census, Harry Lionel (then 5) joined the Royal Navy at the age of 13, was made a Lieutenant in 1896 and later a Commander (captain of HMS Handy in 1902), Richard Busk Paterson (then 7) followed his father into holy orders, and Frederick Neville (then 10 months) went off to try ranching in South America (1899-1902), returned to Guernsey to become a fruit-grower (1902-16), enlisted as a Lieutenant in the Army Service Corps (Horse Transport & Supply) during the First World War and died in 1918 on active service at Le Havre, where he is buried. A later son, John, was knighted. Harry Morland Wells himself graduated at Cambridge and married Frances Ellen Paterson Busk, the daughter of Joseph Busk, a Justice of the Peace in Hertfordshire.

From 1892 to the end of century, the vicar was John William Watney Booth from Surrey, who had been vicar of South Darley in Derbyshire. He was perhaps closer to the people than Harry Wells must have been, and certainly, of the six servants recorded in the 1901 census, five were from Buckinghamshire, one West Wycombe, one Tingewick, and three from Prestwood - the sisters Mabel and Elsie Janes (parlour- and house-maid respectively) and May Ridgley (kitchenmaid). He was very popular with his congregation, as the ornate tombstone in the churchyard and the stained glass window in the church itself, paid for by members of the church, testify. He had graduated from Pembroke College, Oxford. (Revd. Booth later became curate at Monks Risborough, where Thomas Evetts was rector before him.) His wife Alice Margaret was from Lancashire. With them in 1901 were two children, Margaret (1893) and Ralph Hugh (1895), and his unmarried sister Mary Isabel (1864) who had a private income.

A small farm attached to the vicarage had been set up by the 1890s, with outbuildings of timber and slate, flint-work stables, and a pond, where the then vicar Revd. John Booth “kept four cows, pigs, poultry, ducks, turkeys and guinea fowl”. This along with a kitchen garden, protected from inclement seasons by a high wall like that at Peterley Manor, helped keep the household well supplied with food. Booth also bred pheasants and partridge (perhaps in Lawrence Grove Wood where this practice was revived for a while in 2001) for his many shooting parties. He was also a keen foxhunter and played cricket for Kingshill. He was helped in all this labour by just one man, Tom Cummings, who lived in the schoolmaster’s cottage and acted as “ coachman, gardener and gamekeeper – and he sang in the choir on Sundays! ” (Keen, 1996b). Cummings came from Monks Risborough, and had perhaps been recommended by Evetts.

Peterley Manor

Peterley Manor continued to be occupied by tenants of some distinction, largely a succession of scholarly clergymen, as recorded by Keen (2001 & 2002). Peterley House was first tenanted by Mr Wildman Yates Peel in 1852 (then aged 24), after his marriage to a distant cousin Magdalene Susanna Peel in Cheltenham. Mr Peel was a son of Bolton Peel of Staffordshire, while his wife was the daughter of Jonathan Peel of Culham, Oxfordshire and probably known to Evetts. In 1853 and 1854 a son (Reginald William) and then a daughter (Eliza Isabella) were born to them at Peterley, and Wildman Peel was appointed churchwarden. They were well connected, with family in various parts of Britain, including Scotland and Wales, and were related at some remove to Sir Robert Peel, prime minister 1834-35 and 1841-46, the energetic founder of the London police force and the Conservative Party. They moved in about 1856 to Herefordshire and were living in Caernarvonshire in 1870, when he is described as an army captain or "adjutant of volunteers" in the Clackmannan Rifles, and was listed as a subscriber to a monument to Lord Byron.

Revd. Frederick Young, curate of Great Missenden, resided here with five servants from 1858 to 1864. Like Evetts, he had been the first vicar in a newly created parish at Monk Fryston in North Yorkshire in 1846. To supplement his income he once more set up a boarding school for six pupils, mostly sons of colonial administrators living abroad. In 1861 their "private tutor" was Leon Klein (33), who had been born in Poland. Young also continued the management of the surrounding estate, breeding cows, pigs, horses and growing wheat and oats.

The next tenant was Revd. Thomas Fenn, 1865-67, who sometimes assisted at Holy Trinity, including at the marriage of the local builder William Parsons.

From 1867 until 1872 Revd Arthur Hussey, of Eton College and Oxford University, who had taught Thomas Evetts’ son George at St Peter’s College, Radley, near Oxford, took over the lease and re-established the boarding school for ten boys. Pupils were the sons of other gentry, including Evetts’ second son Basil and two from Hampden Rectory. By the time he left, says Keen (2002), “ the house consisted of an entrance hall, dining room with linked conservatory, library, ten bedrooms and dressing room, WC and two staircases. It also boasted an ‘excellent kitchen’, housekeeper’s room, cellars, larder and domestic offices .” He also built a fives court and a cricket pitch, and the school was able to field a side (including Hussey himself) that played other village elevens such as Great Marlow School and Prestwood Church Choir! The Choir eleven in 1871 included sons of several families prominent in the parish in 1851 – blacksmith William Hildreth’s son Owen (15), wheelwright William Janes’ son Peter (29), and Polecat publican Isaac Timpson’s son Herbert (just 10). Cricket continued to be a popular local pastime, with the vicar, John Booth (above), being a particularly noted exponent (Keen, 1996b).

When Hussey left Peterley Manor, the school was closed and it reverted to being a ‘country seat’ of some renown in socialite circles under the energetic tenancy of Sir Charles Lawrence Young, 7th Baronet, for some six years. Among visitors at that time was Sir Henry Irving in August 1874, the year he consolidated his reputation with an acclaimed performance of "Hamlet" in London at the age of 36. Young, a barrister, writer and amateur actor, was formerly resident nearby in North Dean and later in London. His father Sir William Lawrence Young was MP for High Wycombe, and his mother Lady Caroline was co-heir of Hughenden Manor. He succeeded to the baronetcy after the death of both his elder brothers in 1854 during the Crimean War, one at the Battle of Alma and the other contracting cholera at Sebastopol. He was 32 when he arrived at Peterley and a widower, his wife having died very young. He did not remarry until 1881, after he had left Peterley. He co-authored "A Stable for Nighmares; or, Weird Tales" with Sheridan le Fanu and others in 1867, and wrote six plays, including " Jim the Penman ", first performed in New York in 1886 and later made into a silent film starring Lionel Barrymore in 1921. He converted to Catholicism, the Dormers' faith, in 1886, less than a year before he died in 1887. An early photographic portrait done in 1863 by Camille Silvy resides at the National Portrait Gallery.

Tenants thereafter came and went regularly, with four residing there between 1878 and 1900, although each played their part in bestowing patronage on the parish church and social events. Such patronage made a good deal of difference to church funds and local charitable causes. Mrs Agnes Lluellyn, wife of Raymond Lluellyn, for instance, who resided there, after being widowed, for over ten years 1888-98, supported education and “the coal and clothing clubs” (Keen 2002), while holding a celebration of Queen Victoria’s diamond jubilee in 1897 at the Manor for local schoolchildren, each receiving a jubilee mug. At the time of the 1881 census the tenancy was held by John Rochfort Blakiston, son of Major John Blakiston of Mobberley Hall, Cheshire. His wife Georgina was the daughter of Revd. Francis Cubitt, Rector of Fritton. The Blakiston coat-of-arms is described as "Argent, two bars gules, in chief three cocks of the last. Mantling gules and argent. Crest - On a wreath of the colours, a cock gules. Motto - 'Do well and doubt not'".

Blakiston/Rochfort coat-of-arms

In his twenties (in 1863 and 1865) Blakiston played cricket for Cheshire, being principally a bowler. Whether he continued with cricket in his forties at Peterley is unfortunately not recorded.

Community life

With few propertied residents, and the common land gone, a slow decline of rural traditions began. In 1850 spring and autumn fairs were held annually, one on Easter Tuesday and the other on the Monday after Old Michaelmas Day. By 1887 these regular fairs were no longer held, although smaller carnivals continued on and off into the next century. There was, for instance, a harvest festival organised by Revd. Thomas Evetts in September each year for farmers and their labourers. This consisted of a service and sermon, followed by an assembly in a large tent made out of the large cloths used to cover ricks and decorated with laurel branches. There they enjoyed roast beef and plum pudding, punctuated by "jovial toasts", songs and speeches. (Records of Bucks, II, p.47.)

Prestwood could not, however, overlook the Golden Jubilee of Queen Victoria on Midsummer’s Day in 1887, when the whole country celebrated. The Bucks Free Press at the time reported that Cornelius Stevens took on the organisation of this big event, which was funded by a local collection. It opened with a church service by the vicar Revd. HM Wells, the choir provided by children from the “National School” at the church, and then the national anthem was sung, accompanied by Mr Groom on the drum and Mr Bristow on cornet. The Prestwood Brass Band led a procession from Holy Trinity “around Prestwood Common” to Chequers Inn, whence Cornelius Stevens was carried in a chair at the head of the procession to a meadow at Theophilus Beeson’s farm, Andlows (probably Orchard Close or Home Close). Here tea was provided for all the local residents, 600 it is said, with sports and games (tug-of-war, cricket, races) for prizes funded by the collection and donations from Revd. Wells and Lt. Butler Carter, RM. The fun continued until dusk approached at 9.30pm.

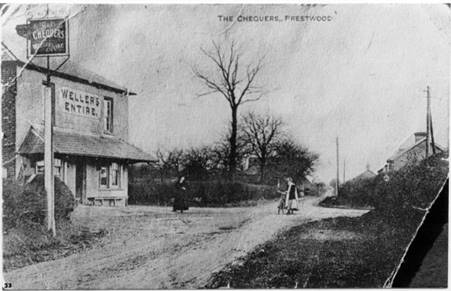

The Travellers Rest public house was built in the early 1850s at the eastern end of what was to be the High Street across the north side of Prestwood Common, and the new Chequers Inn at the same time at the other end (with the new Methodist Chapel, see below, fending both off in between). The growth of Great Kingshill was similarly accompanied by the building, around 1860, of two new public houses, the Red Lion and the Royal Oak, both beside the main route from Prestwood to High Wycombe. (Arthur’s Cottages along this lane had been built in 1856.) A growing community at Bryant’s Bottom also gained its first public house, The Gate, in 1864, ultimately leading perhaps to the demise of the Weathercock on Denner Hill, where the community did not grow as it did in the sheltered valley.

The 1874 Ordnance Survey map shows part of the by-then enclosed Kingshill Common as a designated elm-fringed cricket ground, while part of the recreation ground at the remnant Prestwood Common was similarly used. The Kingshill ground was used from the 1860s onwards, although the local team was originally known as "Brand's Fee", from the old name for Kingshill (see Chapter 3). Later on they were known as "Kingshill Blue Star". Matches were arranged with all neighbouring villages within walking distance (Hazlemere, Hampden, Naphill, and even as far as High Wycombe) in the period August to October (after haymaking). The tie between Kingshill and Prestwood was a particularly fraught local derby. Nearby pubs cashed in on the popularity of the sport by providing refreshments and betting facilities. The unevenness of the pitches, not to mention the odd plantain and daisy, or nettles and bracken at the boundary, no doubt added to the speculativeness of the latter.

The same villages involved in cricket also fielded football teams over the winter, possibly playing on the same fields.

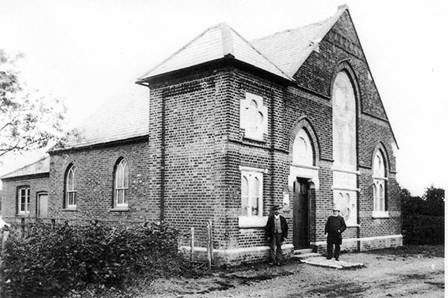

For more everyday communal entertainment the churches were central, providing a context for music and readings, although mostly dominated by religious concerns, and also harvest festivals with free food, children's games and sports. All the churches were well attended throughout the second half of the C19th: Anglican, Wesleyan Methodist (since 1863), Zion Baptist, and the small Primitive Methodist Church at Bryants Bottom (since 1871).

Methodist chapel at Bryants Bottom (right) 1999.

They were the centres of social as well as religious life. Around the 1860s "penny readings" became popular, providing, for the payment of one penny, more secular opportunities to hear readings of poetry and other texts, songs and so on. Although these largely died out by the end of the century, they were indicative of a broader social concern with public education exemplified by the growth of schooling from 1850 (and much more so in the following century) and the growth, in the towns, of Mechanics' Institutes.

Communications

One attraction of Great Missenden, consequent upon its situation in the valley, was communications. The Victorian age was one of rapidly increasing mobility (for those who could afford it), the golden age of the railways and road improvements, and the invention of the bicycle. A major road came through Great Missenden from London and Amersham to Wendover and Aylesbury. In 1850 the horse-drawn coach from Wendover arrived in Great Missenden at 7am to take passengers into the great city, returning therefrom at 7.30pm, the journey taking about five hours. Goods carriers (who also provided a cheap option for passengers if they did not mind sitting among the parcels) operated between Great Missenden and London twice a week.

There was a post office in Great Missenden at Willmore’s ‘grocers and drapers’ with deliveries of letters by the penny post once a day between Great Missenden and both London and Aylesbury (possibly carried by the passenger coach). By the early 1860s a goods carrier was also operating between here and Aylesbury and High Wycombe. Around 1875 the post office was moved to Maximilian Eggleton’s shop, also a grocers and drapers, and an agent for Gilbey’s wines and spirits. By this time telegraphic and postal order services were also on offer. Ten years later the shop business and post office were taken over by Henry William Langton, and pillar letter boxes were being established at outlying villages. Increase in passenger traffic necessitated a much larger horse-drawn omnibus to replace the stage-coach to London.

In 1890 the Metropolitan railway had been built out from London as far as Chalfont, and the omnibus was able to travel twice daily to Chalfont Road station, passengers continuing their journeys from there by train. By 1892 the train was operating as far as Great Missenden itself and the omnibus was no longer needed. There might have been another line from High Wycombe to Great Missenden, too, but Disraeli would not sell land along the Hughenden Valley at a price they could afford, at the same time protecting Prestwood from a direct incursion of the industrial age (Druce 1926 several times refers to the "devastation" caused to the countryside and its flora by the construction of the railways) and condemning it to remain an economic backwater. At this time, too, a full sub-post office was established with its own postmaster and three deliveries a day (much facilitated, of course, by the railway). By the end of the century the horse-drawn carriers to London were redundant, all goods being conveyed much more easily and quickly by rail.

The rapid expansion of communications naturally drew into Great Missenden more businesses and residents. The growing middle class and leisure time brought into existence such businesses as the “fancy repository” (a store for decorative, as against “useful”, goods) which existed from about 1875 to the end of the century, and a taxidermist. More mysteriously, for this very inland area, a “marine store dealer” operated there through 1877 to 1891. By 1895 there was a coffee house, a dairy, a laundry, a coal merchant, a residential hotel, and, a real sign of the times, an electrical engineer and the British Volta Electric Glow-Lamp Co Ltd! At the end of the century a tobacconist and an antique shop had come into existence.

Almost all of this passed Prestwood by. The main route up the hill from Great Missenden to Martins End was still a narrow cart-track and it continued as such across what was once the old common, rutted and puddled. Even so, new houses had sprung up along its route, constituting the beginnings of the current High Street (then Middle Road). Wesley Villa was built there at the beginning of the new century, named after the nearby new Methodist chapel. It was occupied in 1901 by the carter William Peedle, who was also Superintendent at the chapel. The edges of the old Prestwood Common also became new routes, with the construction of Nairdwood Lane on the east side and Moat Lane along the north-eastern edge. New cottages had been built at the corner of the High Street and Moat Lane by the 1880s (now demolished for sheltered housing).

Cottages at corner of High Street and Moat Lane; opposite them is still a field with an orchard beyond that. Late C19th

Similarly the road along the top of Denner Hill followed the eastern edge of the old common there, close to the Weathercock, rather than the old track through the middle of the common past Denner Farm. Generally the roads followed the same routes as previously, however, with the exception of two tracks that disappeared, one being the old Blind Lane to Rignall that set out from Long Row, and the other a track on the western side of Citers Wood. None of these roads were metalled, however, and it was not until a few years after 1900 that the parish even got its first bicycle repairers, William Anderson at Heath End.

A contract for handling post was granted in 1858 (Sheahan, 1862), when the school house at the Church was used. Thomas Ward (just 33) ran the Post Office there until after 1871, as well as being the Registrar of Births and Deaths. His young family kept a servant, Hannah Reeves, who was described as a "letter carrier". In 1871 Thomas Ward was also a land surveyor and rate collector, while his wife Ellen and eldest son Thomas Jr (17) were employed as assistant registrars. Ellen died shortly after this and Thomas eventually re-married and moved to Great Kingshill, where he continued to act as Registrar, his daughter Mary (21) employed as Clerk, and the Royal Oak public house was used as post office. By 1891 the post was handled by the Henry Grover at Collings Hanger Farm, which he had farmed since 1865, letters arriving “ by foot messenger at 8.20 am ”. After his death, Henry's son Arthur took over the farm and the role of postmaster until 1902, along with his uncle Walter. It was not until 1902 that Prestwood obtained its own post office and the postal service was transferred to Morren’s newly built general stores and post-office in the High Street, including a public telephone! (This was on the site of what was to be Draffan’s store, subsequently Rusts supermarket, and now the Co-operative stores.)

ReligionModest as the increase in population was in this half-century, it was sufficient to create demand for places of worship from what was apparently a growing number of non-Conformists (who had always formed a significant part of the population, as we have seen in Chapter 3 from accounts of the Quaker meetings there and the foundation of the Baptist chapel in 1824). In the early 1860s two Methodist chapels were built, one (Wesleyan) in the midst of the new development along the High Street in Prestwood, the other (Primitive Methodist) in the newly expanded community at Bryants Bottom. Shortly afterwards, in 1871, the Zion Baptist Church was also enlarged to accommodate as many as 250, on the original site on the north side of Kiln Road (not, as now, on the south side). (For more information on the Baptist Church and its activities at this time, see Keen, 1996a.) By 1885 the Parish Church also needed enlargement.

The history of the first Methodist chapel was recorded in the leaflet published by Prestwood Methodist Church (1963) on the occasion of its centenary celebration. Those of this persuasion in Prestwood in the middle of the C19th held meetings in their own houses, much as the Quakers had done. T hey then moved to premises at the Traveller’s Rest (run by a Methodist Jabez Taylor), meeting in the skittle alley there. (Wesleyans, at least at this date, did not frown on drink as some do today.) This was obviously seen as a temporary arrangement only, as a vacant site was soon obtained a hundred metres away, part of a field owned by William Cartwright, who had been living at Piggots Farm just outside the parish in 1851. He donated the land legally on 15 April 1863. (His grandson Councillor WO Haines, appropriately, chaired the centenary celebrations in 1963.) By 8 September 1863, in just five months, the church was built and ready for worship!

Prestwood methodist Church c1900

The speed of building depended both on a great deal of voluntary help (women, for instance, gathered stones from fields round about to make up the shell alongside bricks) and on parsimony. The basic structure cost just £130 – under a tenth of the cost of Holy Trinity. There were no pews or pulpit: people sat on forms placed on the trodden earth strewn with straw. (This was the traditional church floor-covering from early times – old “rush-bearing” processions still held in some rural English villages reflect the annual renewal of this “carpet”.) Flooring, pews and a small pulpit were finally added in 1865, having to wait until the extra £60 could be raised. Further additions in 1869 were a gallery, a larger pulpit, and decorative ironwork donated by the blacksmith Benjamin Hildreth. A Sunday School room was built in 1872.

A harmonium was bought for £5 in the 1890s. Until then music was, like the building, a matter of self-help, several members of the church (who included a good number from outside Prestwood, as far away as Speen) being able to play the violin, and at times there were also viols and clarinets. Even when there was an organ this tradition of violin accompaniment continued into the latter half of the C20th. The choir toured the village carol-singing at Christmas, collecting for the Royal Bucks Hospital. (In these days, music was a major pastime of villagers, so that there was no shortage of talents – see Keen, 1998b, on other musical activities at this time.) The Methodist pastor for several years from 1896 was, appropriately, Mr G Church, who lived in Chesham. He walked all the way to Prestwood, a distance of some 10 kilometres, and back each Sunday. On one occasion the snow was so deep that, although there was no evening service and he could get an afternoon start, he did not arrive back home, by the grace of God, until after dawn the following day!

Building in connection with the new church of Holy Trinity continued into the next decade. The architect Lamb was asked to draw up plans for another building, a two-storey house for a new assistant curate, to be built in 1852 on the north side of Prestwood Common (now Flint Cottage). It was built of flint with quoins and dressings in different colours, a fish-scale pattern tiled roof and large distinctive flint crosses set in the gables.

Flint Cottage, upper storey, 2018, clearly in the style of Holy Trinity church

Although most families identified primarily with one church or another, they were not separate communities, sharing social life and even sometimes using churches other than their own, often as a matter of convenience. The blacksmith Benjamin Hildreth, for instance, remained staunchly Methodist but some of his children attended the new Sunday school at Holy Trinity (just across the lane from his forge) and many members of the Hildreth family are buried at that church. Rivalry, as far as it existed, was between church leaders rather than their congregations. While the churches remained important to the end of the century, belief was weakening in many parts of the population and there were signs that secularisation was beginning to become more widespread by the end of the century (Holmes 2010). This most probably reflected a loosening of social and economic ties generally, which began with the Enclosures and gradually eroded the reverence and fear that ordinary workers traditionally showed to their employers. The social contract was becoming economic rather than feudal, as shown by the rise of Trade Unionism in the next century. The churches, especially the Anglican church, was associated strongly with the wealthy residents who dominated leadership, and as respect for the latter declined, so did that for the former. Insofar as the churches remained important at this time, it was increasingly for the social opportunities they provided, the celebration of critical life-events like birth, marriage and death, and, in the case of the new church school at Holy Trinity, educational benefits.

The FamiliesGentry

These noble families were not really part of the ordinary community life of the parish, although they would have been well known by repute, while their power, including land ownership, would have been evident to all the local inhabitants. A few of the more favoured of the latter, as girls in their teens, were temporarily employed as servants in the large houses surrounding Prestwood, so that the life going on within these walls would have been much talked about.

The Hampdens

Donald Cameron of Lochiel died in 1858 and was succeeded by as head of the estate by George Hampden Cameron, while his older brother Donald succeeded as head of the Cameron clan. In a letter in December Benjamin Disraeli wrote to Lord Carrington in favour of George becoming a county magistrate:

"He is a young man of abilities & breeding; & has seen the world. He was private Secy. to Lord Elgin in China, and has been attached to several Missions."

George, who attended Magdalen Collge, Oxford, died unmarried at the early age of 33 in 1874 and was buried right next to the church. His sisters Albinia and Mary Anne Louisa had already died in 1861 and 1864 respectively. The two other sisters had married: Sibella Matilda to Revd. Henry George John Veitch of Eliock in 1865, and Julia Vere to Major-General Hugh Mackenzie in 1870. Sibella died in 1890 but her sister outlived the century.